Author and artist Beth Surdut listens to ravens, and has paddled with alligators in wild and scenic places. She also knows that a nest shouldn't be judged on appearance alone...

Listen:

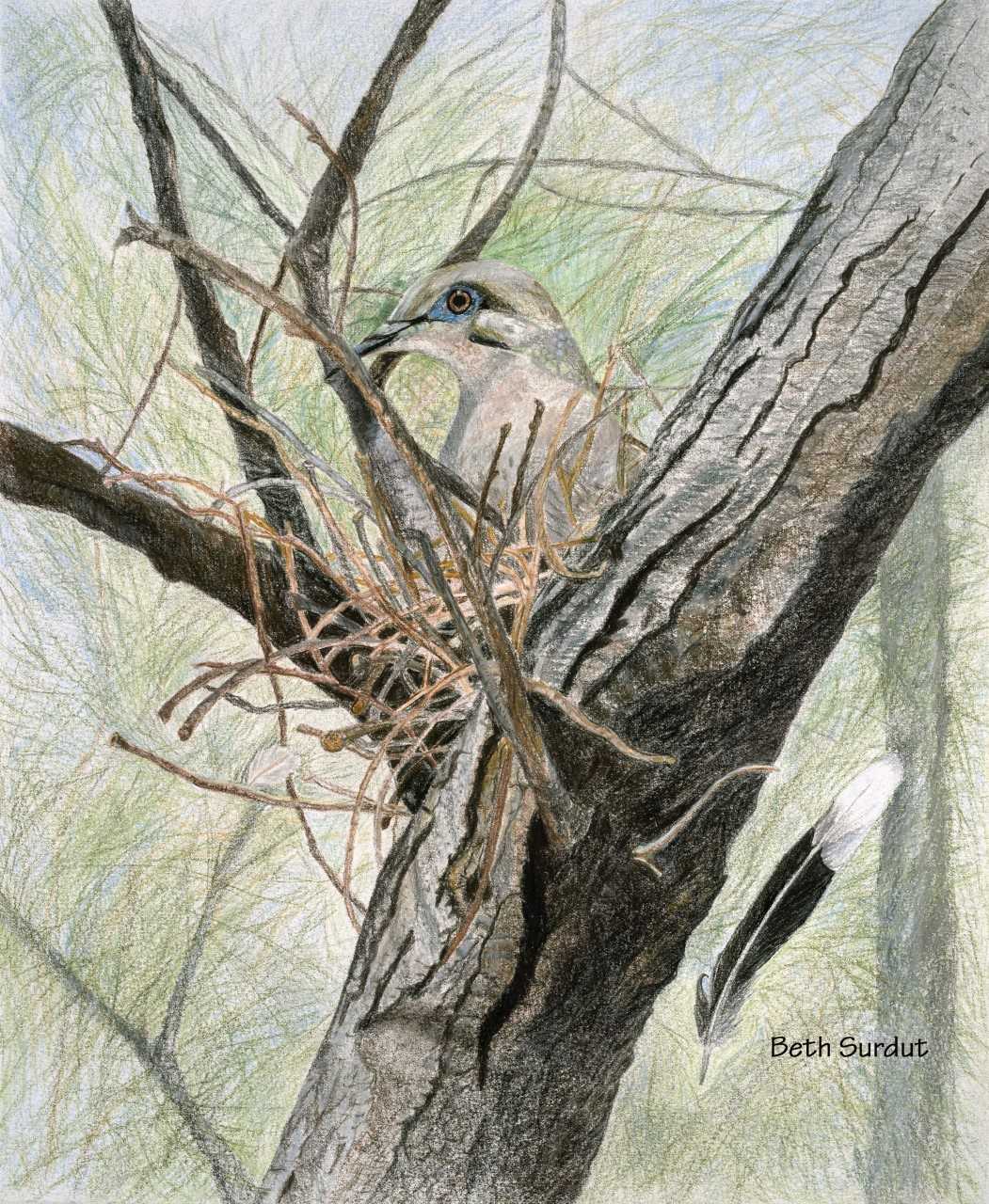

White-winged Doves

© Beth Surdut 2016

High-up in the imposing tamarisk tree outside my bedroom window, a migratory white-winged dove nestles like a plump teapot in the flat saucer where the branches fork. I can see the circle of blue highlighted with lavender around her bright orange eye as she bends her head to rearrange some sticks poking out around her. Her mate arrives with another slim stick in his beak and he stands on her back, drops the stick next to her, and then flies off for what seems to be a very long time before returning with another stick. Again, he stands on top of her, drops his gift, which slides away and shimmies through the air. He does not fly down to retrieve it, but instead returns to his favorite building supply area.

I think they must be new at this, but the more attention I pay, the more I learn that there is a lot that I don’t know about critters, even when I think I do.

By day two of construction, we have had rain—unusual, I’m told. The air sits sweet and sticky on my skin. The dove sits on her sticks. When hummingbirds build a nest, it is compact, dense, designed with tensile strength and lined with soft materials. Clearly, the doves didn’t get that memo. If these inhabitants were humans, they’d be on the road to divorce or looking for another architect and builder.

By day four, the nest looks like a skeleton ready to be filled in. Ms. Dove sits, but doesn’t stay. I take the opportunity to wrap my dressmaker’s tape around the tamarisk’s girth—41 inches tapering upwards to 36. I’m impressed. Though these trees are disliked for their lusty drinking habits and sloppy grooming, I see this one as a tree of life where not only the doves nest, but also, varieties of sparrows, hummingbirds, and verdins perch and call while collared lizards scuttle across the bulky outstretched base.

Later in the morning, as I’m watering the nearby bamboo, the dove pair returns. She nestles, he stands on top of her, his head above hers, and their heads turn towards me in unison as I walk by. The unlined, seemingly rickety, open-air nest that resembles a tangled pile of the game of Pick-Up Sticks proves to be a challenge for me to draw as I try to discern where the elements intersect. What appeared to be a haphazard pile, serves the purpose of holding mother and two eggs—usually two—until little pin-feathered beings grow viable feathers and fly to the ground after two weeks. Both parents watch over them during incubation and through this exploratory period, but doves are food for the Harris’ and Cooper’s hawks in my ‘hood.

Yet even with the losses due to predation, consider the seemingly ubiquitous presence of doves that pollinate saguaros and line the utility wires — I often count more than 20 — and the ones that fly out of the oleanders and eucalyptus as if flushed by hounds when I walk by. Look around for the nests—my neighbor has one built on the electrical outlet cover next to the light by her front door, another in the rhus lancia tree at the corner of her house, and a third on a crossbeam under her patio roof.

Last year, at the edge of a gravel road that leads to my house, the doves chose a labyrinthine mass of cholla with pointy twists and turns surrounded by prickly pear that seemed to present a formidable fortress. Sometimes, if the mother deemed I was too close—she had, after all, chosen a well-trodden path--she would fly off and pretend she was wounded, dropping one white-tipped wing and dragging it as she hopped along on the ground, making herself an obvious target.

A friend came to visit, arriving at my front door, saying “There was a Harris’ hawk standing on the ground just as I made the turn into here. I wonder why?’

I knew why. When I got there, the mother and two babies--they were not old enough to fly—were gone, feathers scattered, some standing upright like little grave markers.

This month marks a year that I’ve lived here, and I see nests being reconstructed in many of the same places. The current babies fledged in that cholla today—the mother was on the nest, father on a branch near her, and I found one youngster walking on the ground below them. I looked up into the trees and the utility pole tops where I usually see the hawks, listened for their distinctive calls, but heard only the drone of bees, the chittering of small birds, and the calls of the white-winged doves.

Throughout the month of March, an exhibition of wildlife drawings and true nature stories by Beth Surdut will be on view at the Kirk-Bear Canyon Library on East Tanque Verde Road.

You can learn about Citizen Science, explore ways to deepen your relationship with nature, and share your stories when Beth Surdut and friends from the National Phenology Network host a presentation on The Art of Paying Attention on Sunday, March 4 from 2 - 4 pm, also at the Kirk-Bear Canyon Library on East Tanque Verde Road.

Visual storyteller Beth Surdut invites you to observe, with unbounded curiosity, the wild life that flies, crawls, and skitters along with us in our changing environment. From exotic orchids and poison dart frogs to local hawks and javelinas, Surdut illustrates her experiences with wild and cultivated nature by creating color-saturated silk paintings and detailed drawings accompanied by true stories.

You can find Surdut's drawings - and true stories about spirited critters - at listeningtoraven.com and surdutblogspot.com.

Beth Surdut's illustrated work Listening to Raven won the 2013 Tucson Festival of Books Literary Award for Non-Fiction. Elements of her raven clan have appeared in Orion Magazine, flown across the digitally looped Art Billboard Project in Albany, New York and roosted at the New York State Museum in an exhibition of international scientific illustrators.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.