The Art of Paying Attention: Mystery in my Pants

© Beth Surdut 2017

I was standing in the drugstore, when I felt a roundish unidentifiable lump inside the upper leg of my jeans. Maybe a crumpled shopping list that had somehow migrated from my pocket? I shook my leg, but whatever it was, stayed put. As I walked, it slid down a bit, and I felt something sharp — maybe a cactus spine? So I didn’t press on it.

I walked outside, sat down in the driver’s seat, and that’s when I felt tiny claws skedaddling sideways around the front of my thigh. Whatever it was didn't head south towards the looser end of my pants leg, so I put my hand over the thing, which immediately stopped, and I felt the outline of a lizard. Certified nature girl that I am, I was curious to see if I could figure out what kind of lizard it was by gently tracing the shape of its head and body through the material of my jeans. Hmm—slender body, long pronounced head…maybe a zebra-tailed lizard?

And then, it squirmed, zhhzzzzzzzhhhz, wriggling rapidly on my thigh, heading for parts most of us consider private.

I am not a squealer. Those panic sounds bouncing around the car must’ve come from someone else, except I was alone with a non-vocalizing reptile. I put my hand on the inside of my leg next to the lizard, forming a wall, hoping I wasn’t squishing delicate and markedly long toes.

The squirming stopped and I said out loud, “Beth, stay calm. You have a harmless lizard in your pants. This must happen to people all the time.”

I thought it was a desert dweller’s right of passage.

Here’s an existential question — would you rather find a live lizard in your pants…or a dead one? I vote for life, so since the busy parking lot didn’t seem like a safe place for a lizard, nor an appropriate place to drop my pants, I started the car and headed home.

Ten minutes later, I parked. Leaped out of the car, kind of like Quasimodo, since I still had my hand clamped to my thigh -- opened the rear door and grabbed a blanket. Now having to use both hands, I wrapped it around me, and dropped my pants in the parking area I share with my neighbors. I picked up my pants. Shook them. Turned them inside out. The lizard had taken off into the dusk without my ever seeing it.

I walked into the bedroom where my jeans had been on a chair before I put them on to go shopping. On the floor, next to the chair, lay the end of a tail with two distinct black bars highlighted by three white ones, confirming my deductions that I had done errands with the fastest lizard in the desert.

The tail-tip that was left behind by a zebra-tailed lizard in Beth Surdut's home.

The tail-tip that was left behind by a zebra-tailed lizard in Beth Surdut's home.

The Latin name for zebra-tailed lizards is Callisaurus draconoides, which translates as beautiful lizard that looks like a dragon. Adults average around 2.5 to 3 inches, not including their thickly-striped and tapered tails, which are at least as long as their bodies.

Although this speedy species is not deeply-studied — “They’re hard to noose,” according to University of Arizona wildlife biologist Matt Goode -- I did find research collected primarily in the 1960s and early 70s. These sprinters have been clocked at an average speed of 23 feet per second! Their legs are significantly longer than other North American desert lizards and they can actually run bipedally—upright on their hind legs. Tolerating hotter temperatures than other lizards, they can lift up their toes, quickly shifting stance the way we do when we’re hopping barefoot on hot surfaces.

They like open spaces and sandy soil to dig in, where, starting in June, they lay clutches of two to eight eggs. During July to November, hatchlings emerge. Like many of the local whip-tailed and spiny lizards that I’ve named Stumpy, these elegant little dragons can confound predators by losing their tails and growing new ones. Coloration viewed from above melds into the desert, but the tail’s underside is especially visible when lifted up and purposely waved. In the 1940s, the geometric pattern and color earned them the name “gridiron” lizards, and the tail-wagging gave them the Spanish name perrito — little dog.

Often, that gentle motion, which reminds me of sea anemones in the water, is the first thing that alerts me to their presence.

One theory is that they are deliberately inviting predators to attack the tail so the rest of the lizard can escape. Another is a “catch me if you can” signal of alertness, which, considering their speed, well, if I were a gambler, I’d bet on the lizard.

Zebra-Tailed Lizard

Zebra-Tailed LizardThe hunting habits of these generalized insect-eaters, who also indulge in plants, is to stand and wait with back legs bent and splayed in what ballet dancers will recognize as a second position plié. The front legs are almost straightened, propping the body upright so that the lizard has a good view and is ready for take-off. If male, that stance shows females his bright turquoise-blue markings around two black bars on his sides, and yellow highlights on his lower torso. These colors intensify during breeding season, with orange on the throat, most visible when he puffs out his dewlap, a pouch under his chin.

Much of their underbellies are varying shades of white, as is the area under the chin, which is decorated with thin charcoal-colored diagonal stripes that look like they were applied with a fine brush. A protective lacy fringe surrounds the eyes and the entire skin is a topographical wonderland of raised designs.

Although I’ve lived around zebra-tailed lizards for two years, I didn’t get to see those details the night a lizard ran around in my pants, but there was a happy ending. We both survived, and that lizard has one heck of a story to tell.

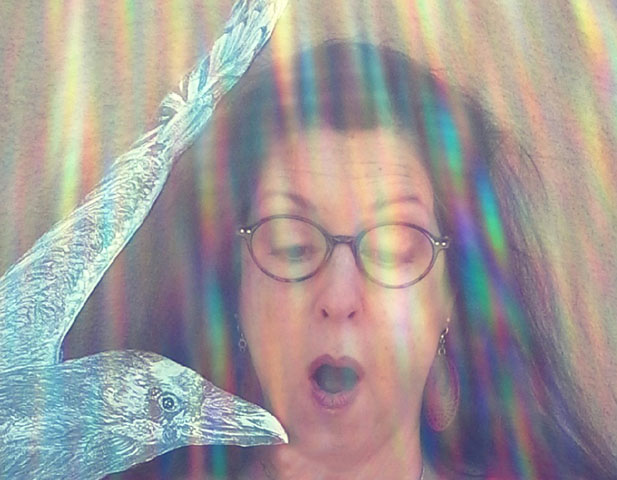

Visual storyteller Beth Surdut invites you to observe, with unbounded curiosity, the wild life that flies, crawls, and skitters along with us in our changing environment. From exotic orchids and poison dart frogs to local hawks and javelinas, Surdut illustrates her experiences with wild and cultivated nature by creating color-saturated silk paintings and detailed drawings accompanied by true stories.

You can find Surdut's drawings - and true stories about spirited critters - at listeningtoraven.com and surdutblogspot.com.

Beth Surdut's illustrated work Listening to Raven won the 2013 Tucson Festival of Books Literary Award for Non-Fiction. Elements of her raven clan have appeared in Orion Magazine, flown across the digitally looped Art Billboard Project in Albany, New York and roosted at the New York State Museum in an exhibition of international scientific illustrators.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.