“Never saw the inside of a violin in all the years I’d played, but I saw plenty of insides," Dr. Bloomfield said. That changed when he started at the repair shop.

“Never saw the inside of a violin in all the years I’d played, but I saw plenty of insides," Dr. Bloomfield said. That changed when he started at the repair shop. Ned Bloomfield leans over a dismantled violin andadjusts the tuning pegs with a surgeon’s precision and tools.

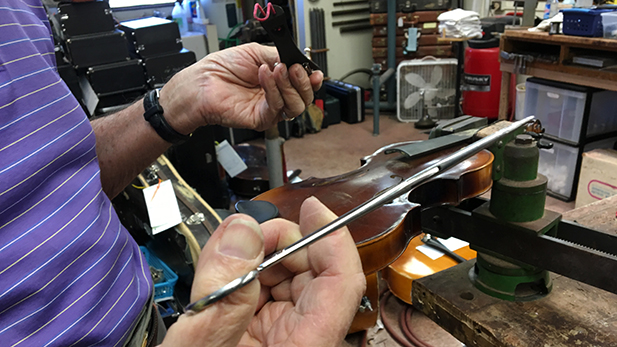

The scissors-like hemostat is meant to tie knots and clamp bleeding blood vessels, but it works just as well for violin surgery.

“You know, school kids are very inventive on how to destruct a violin, really,” Bloomfield said.

The tool is a transplant from Bloomfield’s career before the 85-year-old became the longest-standing volunteer in the Tucson Unified School District’s instrument repair shop.

The trailer in the parking lot of the district's educational resource center is the hub for the care and cleaning of the district's 13,000 musical instruments.

“The instrumental repair shop is absolutely essential,” TUSD Fine Arts Director Joan Ashcraft said.

Listen:

Most school districts outsource their repair work, but with the large number of instruments in TUSD, it saves money to have the work done in-house. Two paid employees and a handful of volunteers keep the instruments circulating into and out of the crowded shop.

A stack of bassoon cases brushes the ceiling in one corner, bows of varying lengths hang from the end of a shelf and a banged-up tuba is one of several marching veterans that need dents reversed.

Bloomfield, a violinist and retired obstetrician and gynecologist, has doctored an estimated 17,000 instruments.

“The similarities are that the patients come in and they’re a broken a little bit, and they need something fixed, and that’s what the docs do,” Bloomfield said. “They fix these parts of people that are not just whole, just like the instruments.”

"If you get something stuck inside of the violin, you don’t have to break it open to get it out," Bloomfield said of one use for hemostats outside the medical field.

"If you get something stuck inside of the violin, you don’t have to break it open to get it out," Bloomfield said of one use for hemostats outside the medical field. Even before his first violin lessons in the fifth grade, Ned Bloomfield plucked at strings.

“I used to stretch rubber bands on the bedposts and play a little tune,” Bloomfield remembered.

He graduated to the violin in 5th grade and took classes through high school. Bloomfield set aside his bow until he joined an orchestra at what is now called Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, where he studied medicine and completed his residency in obstetrics and gynecology.

He established a private practice in Tucson in the 1960s, where the weather was more conducive to tennis than violin playing. But when his partner, a flutist, found out he was a violinist, they began to play duets off the court.

That was the beginning of the barefoot quartet, a rotating group of chamber musicians who have taken off their shoes to play in Bloomfield’s living room for about 40 years.

Bloomfield has hosted chamber musicians in his living room since the 1960s. The informal group plays in stocking feet and usually stops for tea.

Bloomfield has hosted chamber musicians in his living room since the 1960s. The informal group plays in stocking feet and usually stops for tea. Some nights, Bloomfield would get a phone call that one of his patient’s was in labor.

"I would say, 'keep playing, ladies. Keep playing. I’ll be back.'”

“Then we’d do trios until he got back,” said Ellen Caldwell, who plays the violin in today’s iteration of the quartet. There’s also a violist and a cellist.

“Some have passed on and some have passed away, but we’ve always found somebody,” Bloomfield said.

Hear the barefoot quartet play Mendelssohn

Bloomfield retired from medicine in 1998. There were fewer interruptions. The quartet could meet during the day and he had more time for model boat building, another hobby in which Bloomfield carefully fashions small pieces into a whole.

He also started volunteering in a friend’s classroom, tuning instruments and adjusting postures. At the end of the school year, he delivered the instruments to the repair shop. His friend warned Bloomfield, once dropped off, she might not see them again for six months.

“That suddenly set off a lightbulb–oh boy– fixing something, I love to fix things, I’ve been fixing things all my life.”

When Bloomfield wandered into the shop, Sean Randel was in his second year as head repair technician. They would later find out this was a second introduction.

The pair have the story well rehearsed. It’s one of their favorites to share with visitors to the shop.

After 17 years, Randel said Bloomfield now has the skills of luthier. He can take tops off instruments, repair cracks and install strings.

“They’re quiet until we finish fixing them, then they’re pretty noisy,” Bloomfield said of the instruments. He said patients were often the opposite.

When Bloomfield started, the instrument shop was responsible for fewer instruments.

The district began Opening Minds Through the Arts in 2000. The fine arts program brings dance, music, visual arts and theater to every non-magnet elementary and middle school in the district.

Even as the program has earned national recognition, the budget for fine arts in the district has shrunk more than 25 percent in the last five years. The department no longer has money to purchase new instruments, although demand has risen. Ashcraft estimated 90 percent of students rely on the district to provide an instrument.

“Our philosophy is we want every student to have the opportunity to play an instrument, and that opportunity begins in fourth grade,” Ashcraft said.

This fall, the department asked for donations from the community and received close to 150 instruments -- from violins to a mountain dulcimer.

The repair shop evaluates and fixes the donated instruments before they are handed to students. Its budget for repair supplies this year is more than 80 percent spent Ashcraft said.

Several years ago, when the repair budget was reduced to zero, Bloomfield organized a fundraiser among his friends and collected $31,000.

“He brings us a lot of joy, and we hope we can return some of that to him,” Ashcraft said.

On a recent day, Bloomfield unpacked a donated violin from a velvet-lined case. A tangled mass of hair hung from the bow like a beard.

He trimmed the thread back and determined this one was worth saving for a future violinist in the district.

“I’ve always maintained that this job has done more for me than I have done for this job. It’s kept me interested, alive and thinking,” Bloomfield said.

For the foreseeable future, he will spend a few hours each weekday in the repair shop.

“That’s one of the most important parts of aging that I’ve found is to continue to be involved in something that you love and contribute to the community in which you live.”

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.