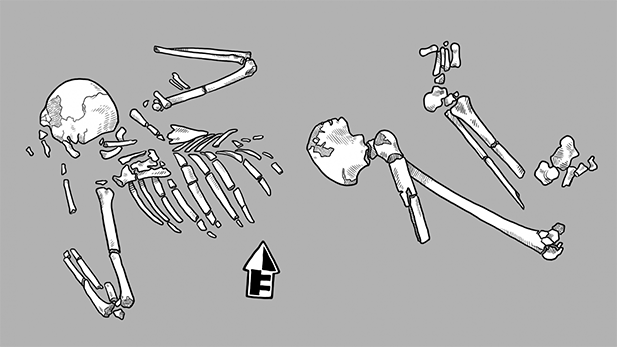

An example of atypical body placement from Early Agricultural Period (2100 BC - 50 AD) sites in the Sonoran Desert. The body is prone and splayed.

An example of atypical body placement from Early Agricultural Period (2100 BC - 50 AD) sites in the Sonoran Desert. The body is prone and splayed.Arizona Science Desk

Bodies buried in atypical ways — in unusual postures, without funeral rites — could suggest a history of revenge and blood feuds in certain ancient Sonoran Desert cultures, according to a paper by University of Arizona bioarchaeologist James Watson and doctoral candidate Danielle O. Phelps.

The research was published in the August 2016 edition of Current Anthropology.

All of the burials studied occurred during the Early Agricultural Period, from 2100 BC to 50 AD. Spread over 150 miles and 2,000 years, they shared one key quality that Watson said “set them apart from others.”

“They were placed very haphazardly — obviously, some level of disrespect went into how the individual was interred," Watson said.

One body appeared to have been thrown headfirst into a grave. Others showed various signs of disrespect, as though they had been placed haphazardly instead interred with proper burial rites.

The Early Agricultural Period refers to the earliest transition from hunting and gathering to irrigation agriculture in the Southwest United States and Northwest Mexico. The authors argue that this shift might have amplified frictions within Sonoran societies and increased pressures on warriors to boost their prestige through defiant acts.

A rude burial would have sent such a message — and deeply distressed the victim’s family and community.

“So, killing them is one thing, burying them improperly is another, but then not knowing — the family not knowing where that individual is, to be able to try and inter them properly — is just that other layer that they’re adding on top of it,” said Watson.

Across cultures, burial processes convey community roles, social importance and metaphysical worldviews. “A part of mortuary ritual is that you’re publicly signaling something — you’re trying to reinforce something, you’re trying to distinguish yourself, you’re trying to do something,” said Michigan State University anthropologist Lynne Goldstein, who served as a reviewer on the paper.

Many societies view funeral rites as essential to a peaceful life-death transition and believe that denying them invites disaster for both the living and the dead.

As signals go, it’s a pretty strong one.

“Not that these people just died for that reason necessarily but, in terms of these unusual or atypical burials, they’re sending a particular kind of message,” said Goldstein.

Other studies have suggested that atypical burials play a key role in a social self-correction process — the final step in removing a deviant element, for example. But for their explanation, Watson and Phelps took a page out of evolutionary biology. To them, these burials fit a pattern defined by costly signaling theory.

Creatures throughout the animal kingdom, including humans, use nonverbal signals to influence each other. But, like a knockoff Rolex, signals can be deceptive, so some creatures use riskier strategies to reassure their target of their sincerity. For example, bright plumage might help a bird attract a mate, but it also invites the unwanted attentions of predators.

In short, when a creature puts its proverbial money where its mouth, beak or snout is, it assures the recipient that it means business.

According to Watson, causing someone’s violent end, and then denying them a proper burial, sent a clear and advantageous signal: namely, that you were an impressive warrior, even an asset to the clan or social group. But it also entailed risk — the kind that could spiral out of control.

“Revenge is a great explanation for not only why you’d kill somebody, but then, in addition, you have the potential to invite revenge back on you, and I said, ‘Boy, this sounds a lot like costly signaling,’” he said.

Watson grants that these reasons amount to suppositions, but he stresses that they parallel blood feuds in tribal societies elsewhere at similar stages of development.

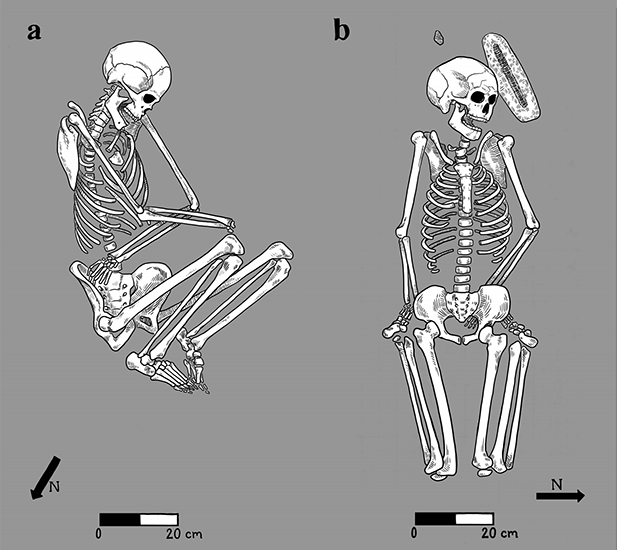

Examples of typical body placement from Early Agricultural Period (2100 BC - 50 AD) sites in the Sonoran Desert: a) flexed position, on its side, with arms folded over, and b) flexed supine position, hands under feet, with household object.

Examples of typical body placement from Early Agricultural Period (2100 BC - 50 AD) sites in the Sonoran Desert: a) flexed position, on its side, with arms folded over, and b) flexed supine position, hands under feet, with household object.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.