VIEW LARGER

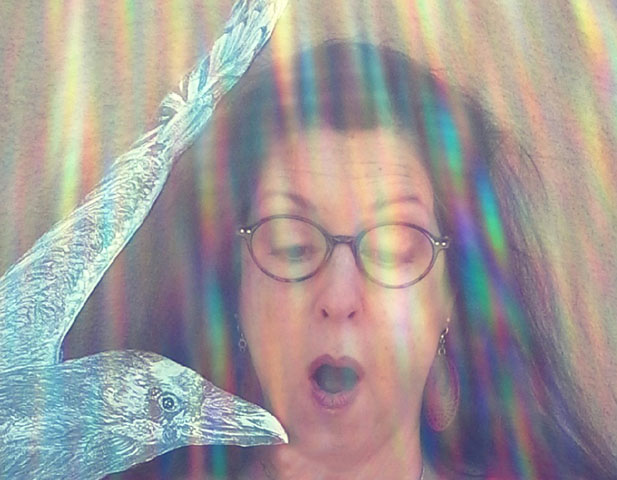

VIEW LARGER Author and wildlife illustrator Beth Surdut listens to ravens, and has paddled with alligators in wild and scenic places. She also tracks a master of camouflage, right here in Tucson...

Paying Attention: Great Horned Owls © Beth Surdut 2016

August 2015 — At the edge of nightfall, I could sense a storm coming—when you live in the desert, you can smell moisture like a hound picks up scent. My neighbor, Keith, knocked on my door. “I hope I’m not bothering you. You told me to come get you,” he said. “There’s an owl!” I followed him—not far—and he pointed at the unmistakable shape of a Great horned owl perched atop a utility pole. “It was on our roof,” Keith whispered. “There might be two of them.” The owl turned its head towards us. Lightning crackled and cut the sky into jagged pieces, but the owl stayed in place and so did we.

When I started asking about the owls over a year ago, neighbors showed me the large twiggy nest that most likely started out as a Harris’ hawk’s. Owls don’t build; they move in. Looking like a stack of kindling with stuffing, it sat very high up in a shaggy bark eucalyptus tree where the owls used to be. I saw the ancient pine where the owls no longer showed up. Every place was past tense.

VIEW LARGER

VIEW LARGER A year later, I photographed an adult owl perched like a sentry near the old nest. A neighbor, walking her little meal-sized dog, said that she’d talked to one of the owls and it seemed to listen to her. I think it was probably scoping out the pooch.

VIEW LARGER

VIEW LARGER A few days later, at dusk, at the turn to my house, a Great Horned Owl flew from behind me, just a few feet above me, to my right, and landed in a nearby tree. It seemed to be looking at me where I’d stopped on the dirt road, but then a small sound brought my glance down. Looking up at me from four feet away, a juvenile owl’s big eyes stared as it hopped once, an ungainly motion, stopped, hopped the other way, and looked at me with what can best be described as puzzlement.

Neither of us knew the exact etiquette in this situation, but the adult did. Flying in a big loop, it returned, waited, and then flew again, this time followed by the little one I’d almost stepped on.

During the rest of this last summer and into fall, I learned where they slept during the day. Until the water became too cold, my end-of-day ritual was to go for a swim near their favorite trees, wait for the owls to wake up and call to each other. They became used to me, no longer squawking an alarm call at my presence. Just before full darkness, they’d fly out to hunt.

I named them Pancho and Lefty. Pancho is larger and older, with a deeper voice and bolder than shy young Lefty, who tended to favor bushier leaf cover before eventually flying to more exposed branches. Pancho always looked down at me as if I were some errant peasant who had wandered into the royal realm.

They are magnificent, standing 18 to 24 inches tall. In flight, they have a wing span of 3 to 5 feet. Their coloration blends into tree bark so perfectly that only a call, a head turn, or leaves rustling when there’s no breeze, shows me where they are. When the owls are awake, black-centered yellow eyes stare down at me straight on, because an owl is unable to move its huge tubular eyes independently. To see, it swivels its entire head as much as 270 degrees.

From underneath, the rear view looks like so many delicately striped petticoats and soft white bloomers covering sturdy legs ending in toes, sensitive as a human’s palm, that can clamp with unrelenting pressure. The gun-colored talons, one of them serrated, are so sharp they can puncture a spine.

VIEW LARGER

VIEW LARGER Photo of "Pancho" by Doris Evans

Owls excrete bright white splashes of uric acid creating a map on the ground leading to grey pellets of indigestible animal parts. These densely packed one-to-two-inch pods are stored in the gizzard, then gently regurgitated about 10 hours later.

When people talk about a girls’ night out, it usually involves shopping, spas, drinks. My friends come over to see what an owl gacked up.

“Packrat,” said wildlife photographer Doris Evans, peering at the tiny jaw fragments and bones lined up next to fur on my work table. “Look at the shape of the teeth and the yellowing--that signifies rodent,” she said.

The death of one animal fosters life in another. Fifty percent of baby owls die in their first year, the majority from starvation. If they survive that year, these powerful predators can average 15 years in the wild, more if food is abundant. That is, if they avoid being hit by cars and eating rodents poisoned by humans.

The last time I stood listening to Pancho and Lefty in a star-filled night, I retrieved another pellet, curious to see who’s inside. Tracking this gives me clues to the state of my small patch of environment and pieces of the puzzle of how to care for it. I have noticed that the rabbit population has diminished greatly and now I see mating pairs as creators of food for the local raptors.

Pancho and Lefty disappeared end of October, the youngster’s time having come to find its own territory, which might be only a mile away. Over the next weeks I would stand under the trees where they had slept, hoping one of them would return. I spotted a flutter, higher than any ladder would reach. Even so, I stretched up my arm, so wanting to bring that owl feather home.

Right about now, mid-December, you may hear owls calling to each other with raucous insistent sounds. Two weeks ago, at one o’clock in the morning, the hoots were so loud that they boomed through my closed doors and windows. This is courtship, the owls elevating their hormones for the next breeding cycle.

Look for big nests. Form a citizen’s science brigade with your neighbors, as I do. With patience and luck, you may find a Great Horned owl or two. It’s not that they are rare, but that they are so very adept at camouflage.

Recently, in a cold dusk so windy I thought it snatched up my voice when I hooted, two Great Horned owls flew in close to me and swooped upwards into the trees where I’d watched Pancho and Lefty so often. My smile was as wide and bright as the new moon sliver in the darkening sky. - Beth Surdut

Visual storyteller Beth Surdut invites you to observe, with unbounded curiosity, the wild life that flies, crawls, and skitters along with us in our changing environment. From exotic orchids and poison dart frogs to local hawks and javelinas, Surdut illustrates her experiences with wild and cultivated nature by creating color-saturated silk paintings and detailed drawings accompanied by true stories.

You can find Surdut's drawings - and true stories about spirited critters - at listeningtoraven.com and surdutblogspot.com.

Beth Surdut's illustrated work Listening to Raven won the 2013 Tucson Festival of Books Literary Award for Non-Fiction. Elements of her raven clan have appeared in Orion Magazine, flown across the digitally looped Art Billboard Project in Albany, New York and roosted at the New York State Museum in an exhibition of international scientific illustrators.

And, if you are visiting California, Beth's drawing of a Townsend's Big-Eared Bat was chosen for inclusion in the 2016 Los Angeles Billboard Creative Show, and will be on view on Melrose between Larchmont and Gower through January 8th.

Become a Master Naturalist! They are seeking 20 or 25 people to join the inaugural training class of the Pima County Master Naturalists, an affiliate chapter of The Arizona Master Naturalist Association. Upon completion of the 60-hour training course, certified Master Naturalists will give back 60 hours of volunteer service to partnering organizations in greater Tucson each year. The deadline to apply for the January class in 12/31/16 at 5pm.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.