A Spanish as a second language class with Haitian students at the Cafemin shelter for migrants in Mexico City.

A Spanish as a second language class with Haitian students at the Cafemin shelter for migrants in Mexico City.

Mauricio Quesada pointed at a poster he drew as he shared his personal story with a dozen classmates. Like most of them, he had migrated from Central America to Mexico City. Until last summer, he lived with his wife, two children and grandson in El Salvador.

He was a teacher, and traveled four hours every Monday from his home to the school where he taught social studies to elementary and secondary students. When he got home one Friday in 2014, his wife told him someone had left envelopes under their door. It was from the MS13 gang.

“They wanted me to pay them $150 every two weeks,” Quesada said.

VIEW LARGER Desks at the Cafemin migrant shelter in Mexico City.

VIEW LARGER Desks at the Cafemin migrant shelter in Mexico City. As a teacher, Quesada made a relatively good living of $750 per month. For a while, he was able to pay. But he was the only breadwinner in the family, and when he started leaving the gang $85 or $75, two young males on bicycles began following him to work.

Quesada was worried about his family, so last summer his wife and kids moved to his in-laws’ house and he left to look for work in Mexico.

Authorities in Mexico rejected his asylum application, saying he had provided no evidence of hardship. "What more evidence than being 50 years old and leaving a good job that paid well?" he asked.

Quesada assumed that the only evidence they would accept would be a missing limb or bullet wounds on his chest.

“I came to Mexico only because I’m looking for a safe place for my family,” Quesada said. “That’s my only goal.”

Across the U.S. and here in Arizona, cities are debating whether they should continue offering safe havens to undocumented immigrants in light of President Donald Trump’s policies. Across the border, Mexico City is implementing “sanctuary city” policies of its own.

Mexico received almost 9,000 asylum applications last year. And the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees expects that number to more than double this year, in part because the U.S. has become less appealing.

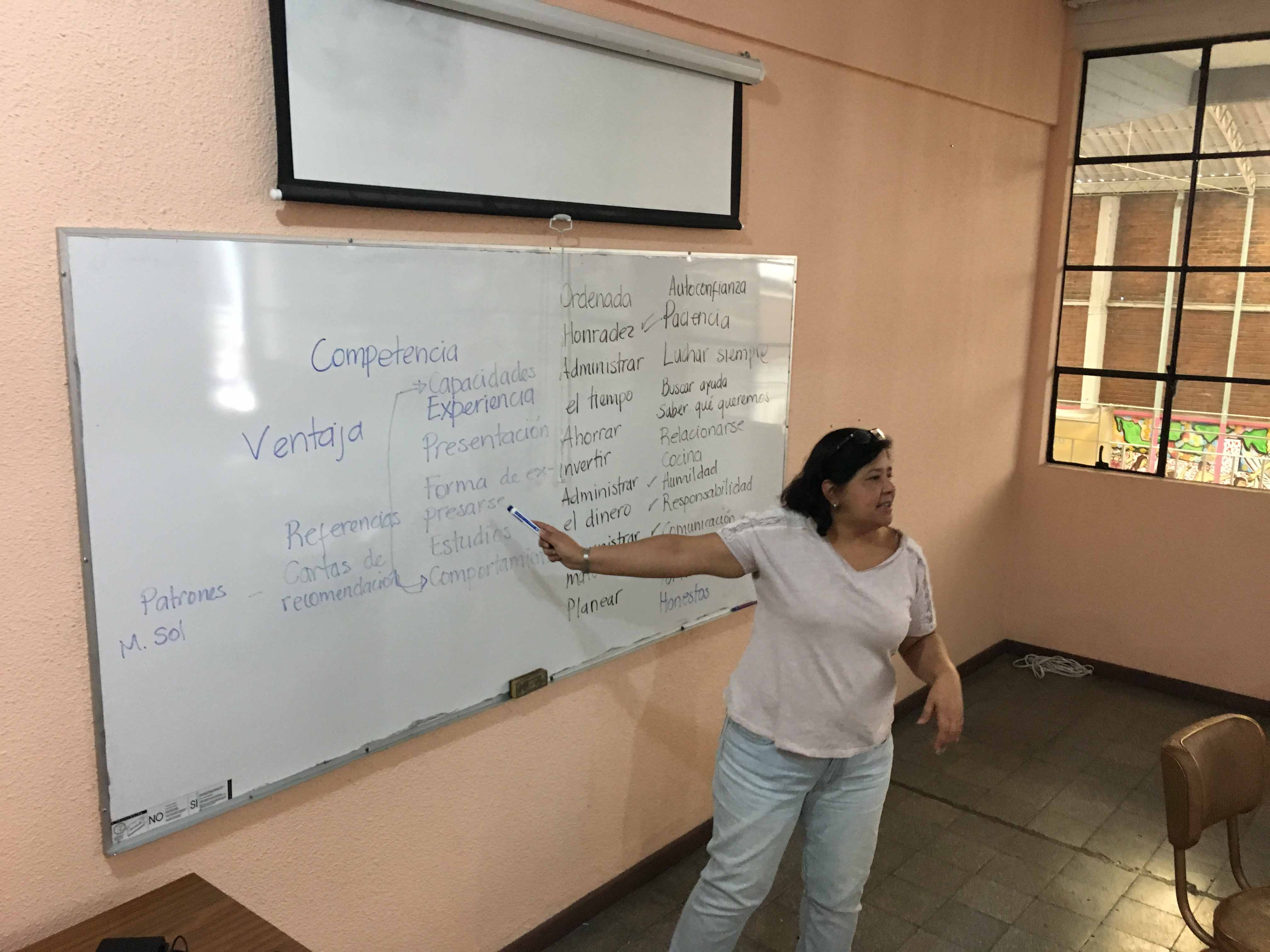

VIEW LARGER Patricia Castilleja teaches workplace training classes at the Cafemin migrant shelter in Mexico City.

VIEW LARGER Patricia Castilleja teaches workplace training classes at the Cafemin migrant shelter in Mexico City. Within Mexico, the capital city has become a certain kind of destination through policies that resemble those of U.S. sanctuary cities.

Mexico City employees are instructed to not ask for a person’s migratory status, said Ruben Fuentes Rodriguez, who heads the city’s agency overseeing aid to migrants.

Mexico City is the only local government in the country that issues ID cards to migrants. This gives them access to public health services.

The city also gives grants to help migrants start their own businesses. In 2015, the city funded more than 350 projects, such as a shoe repair shop, a beauty salon or a food cart.

“The spirit is to give them some sort of incentive to help them join the city’s economy in a formal way,” Fuentes Rodriguez said.

These policies are a result of the city’s Intercultural law, or “Ley de Interculturalidad,” of 2011.

Elisa Ortega Velasquez, a researcher focusing on migration issues at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, said the city has more liberal tendencies than most of the country.

"It's been about 20 years that Mexico City is governed by left, which is keen to provide citizens with some rights, such as gay marriage and abortion,” Ortega Velasquez said.

And yet many advocates complain that migrants often don’t get the services the law affords them or that some local officials report them to federal immigration authorities.

“There are two speeches,” said Gabriela Hernandez, who runs Tochan, a shelter for migrant men. “There’s the one that the mayor gives, and there’s the one that his public servants give.”

Hernandez said she gives the mayor the benefit of the doubt. She said she believes he wants to help, but just lacks follow-through. Hernandez would like to see Mexico City become a migrant city -- but in practice, and not just in political speeches.

The class that Quesada is taking could make him eligible for the city’s business-grant program. For his presentation, he drew a mountain with the sun shining on top.

Quesada said he wants to bring his wife and sons from El Salvador to Mexico, and he has a long road to travel and little time to rest.

“I can’t stop walking until I see the clarity of the sun,” he said.

But Quesada’s needs are immediate, and the city’s grant program won’t deliver until July at the earliest. He said he recently got a job as a carpenter, but that he still hasn’t collected enough money to send his family.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.