A woman crosses the street in Nogales, Sonora.

A woman crosses the street in Nogales, Sonora.

A promised crackdown on illegal immigration is altering the demographics of the borderlands.

Ricardo, 35, stepped off a white, government deportation bus and crossed into a chaotic Nogales, Mexico, on a night in late May. He was disoriented. His upper body was wrapped in a black support vest; he said it was issued by a hospital in Denver after he hurt himself when he fell from a scaffold while hanging drywall.

He stood outside Mexico’s immigration office at the border in a gritty white hallway with narrow steel benches bolted to the tile floors. There were two doors: one leading to Mexico’s side of the port of entry, the other into Mexico. A beggar chanted softly under the harsh fluorescent lights outside a border dentist office.

Ricardo still bore stitches in his stomach and on his right side.

His story is a common one. He’d crossed into the U.S. 10 years ago on a tourist visa, stayed illegally and sent money back to his wife in Mexico, until he was injured.

VIEW LARGER Migrants wait in a chapel inside the Nogales, Sonora-operated Juan Bosco migrant shelter.

VIEW LARGER Migrants wait in a chapel inside the Nogales, Sonora-operated Juan Bosco migrant shelter. After he was hurt, Ricardo said immigration agents were called and appeared at the hospital. He was detained there, bused to Nogales and ended up here.

Federal records show that apprehensions along the Mexican border are down, way down. Border Patrol charts on the numbers show lines plummeting in near dead-vertical drops from 47,000 arrests in November to 11,000 in April.

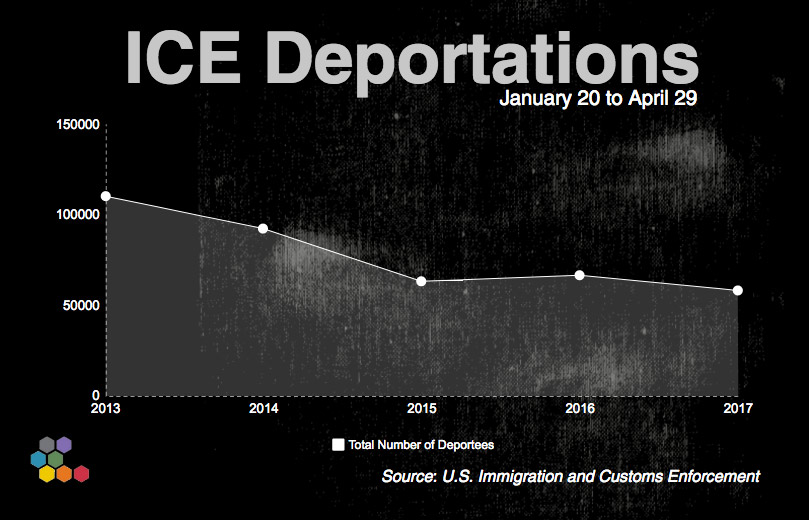

At the same time, Immigration and Customs Enforcement numbers have stayed much the same under President Donald Trump as they did under former President Barack Obama: 57,000 this January to April, and 66,000 in the same four months of last year.

Taken together, those numbers create a new reality on Mexico’s border: A changing demographic of deportees hovering on the foreign streets of a country where they were born and separated from a country they called home.

Home, away from home

VIEW LARGER Immigrants participate in a prayer exercise at the Kino Border Initiative in Nogales, Sonora.

VIEW LARGER Immigrants participate in a prayer exercise at the Kino Border Initiative in Nogales, Sonora. A volunteer leads 40 people through a prayer exercise on a recent day at the Kino Border Initiative, a church-run kitchen for deportees and those heading north. People awaiting a hot meal giggle as the volunteer leads their chant.

The shelter serves up about 46,000 meals a year, and this year is on pace to match that, despite dropping arrests at the border.

“This year we’re serving more people who had been living in the U.S. for a number of years and then were detained and deported,” said Sean Carroll, executive director of the group.

VIEW LARGER Hernandez was recently deported from the U.S. after a domestic dispute with his spouse in Ohio.

VIEW LARGER Hernandez was recently deported from the U.S. after a domestic dispute with his spouse in Ohio. Arnulfo Hernandez stood outside the shelter wearing a rosary over a rock T-shirt and a worn towel draped over one shoulder.

“I was arguing with my wife, you know, just words, and my neighbors called the cops on me,” he said.

He’d lived in Ohio for 18 years. He’s lived in a Nogales, Mexico, shelter for the past two weeks. Now, he says he’ll probably return to his mother’s home in Oaxaca.

“I wanted go back to the U.S., but not right now. I don’t think it’s a good idea right now,” Hernandez said.

“This year we’re serving more people who had been living in the U.S. for a number of years and then were detained and deported,” Sean Carroll, executive director of the Kino Border Initiative

Ricardo, who was deported after being injured, said sheepishly he was going home to a small town in southern Sonora, broke and injured, his only belongings stuffed into a clear plastic bag emblazoned with the blue Homeland Security Department logo.

He didn't want his full name used, he said, because he’ll probably try to cross again.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.