The San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area.

The San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area.

A study published in October set out to answer a question of special importance to dry regions like Southern Arizona: How will climate change affect what happens to water recharge in Western states?

The short answer, according to University of Arizona researchers, is that in the future there will be about the same or more recharge in the north, and states in the south will see less.

“In the Western United States, as a rule, sort of north of a line that you could draw, say, from Sacramento to Denver, precipitation and recharge are likely to either increase or stay about the same as they are today,” said Thomas Meixner, the second author on the study. “South of that line, you get to areas increasingly where recharge will decline, perhaps significantly, compared to present-day estimates of recharge.”

That’s important in a state like Arizona, where more than 40 percent of the water supply is pumped from underground aquifers.

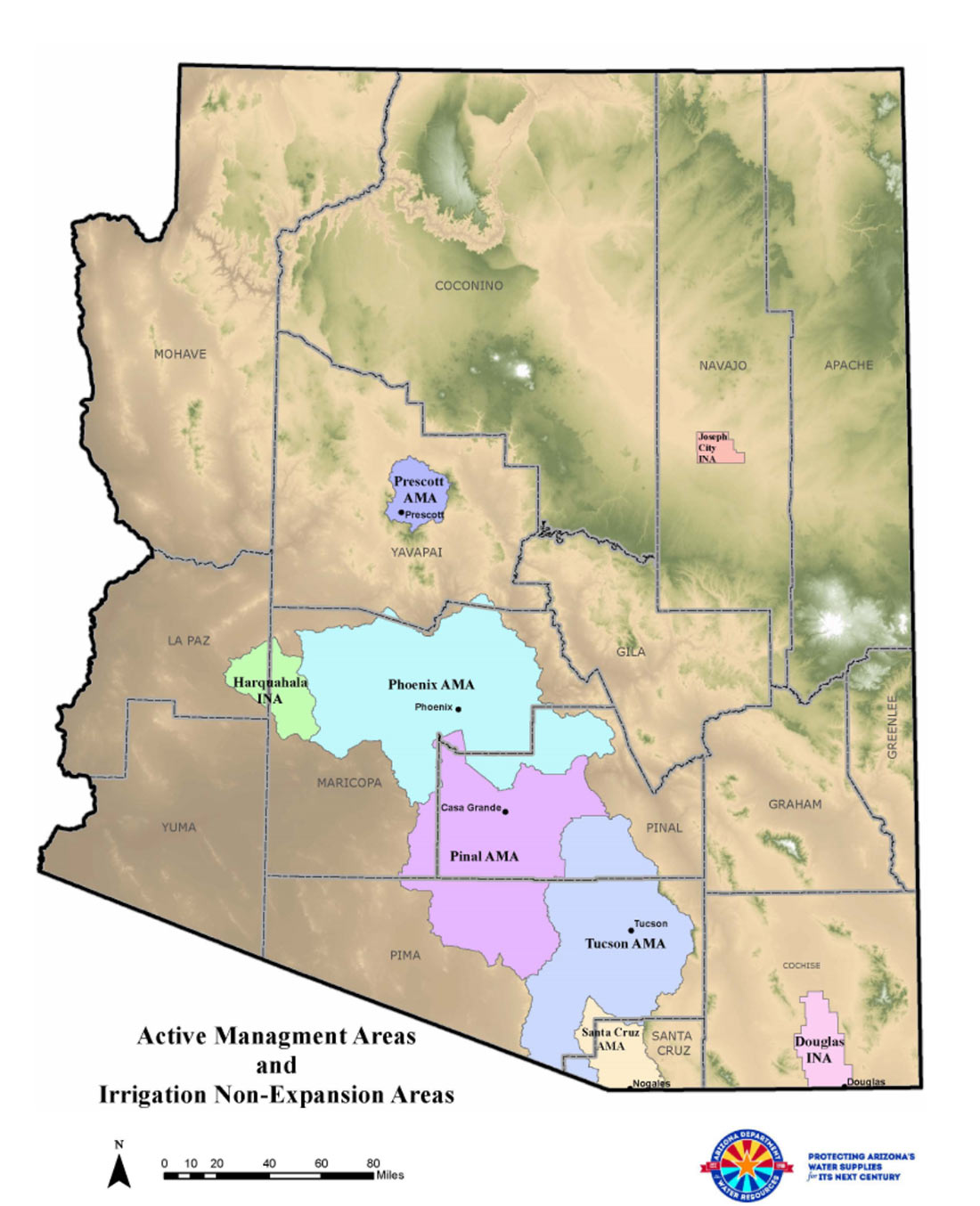

It also could also be tougher on certain regions, especially those outside of urban areas. Meixner, a professor in the department of hydrology and atmospheric sciences, said active-management areas (AMA) like Tucson implement recharge projects and get water from more than one source, including the Colorado River. Areas in Southern Arizona outside of an AMA rely completely on groundwater.

VIEW LARGER An Arizona Department of Water Resources map of Active Managment Areas in Arizona.

VIEW LARGER An Arizona Department of Water Resources map of Active Managment Areas in Arizona. Some residents in Cochise County have seen wells dry up in recent years for a variety of reasons, he said, and the research suggests that may happen more frequently in the future.

Phenomena like that present challenges for water management.

“If you’re only dependent on local groundwater, you don’t have a diverse portfolio. … Like anything in life, a diversified portfolio protects you more against risk than not.”

Much research has been dedicated to understanding how climate change might affect the flows of the rivers like the Colorado, Platte and Sacramento, Meixner said, but groundwater has received less attention.

One reason is that it’s harder to study than surface water: “We can’t go there.”

And that also means the effects on underground water resources may be less obvious.

“Impacts on groundwater are sort of a slow-motion train wreck. You don’t feel things immediately, but groundwater levels slowly decline.”

Part of the bigger picture, he said, is that many regions in the West are already facing a difficult water-resource puzzle.

“In parts of the West, we’ve been withdrawing water faster than it’s being recharged,” Meixner said. “We already have a hard job. If I was a water manager I’d say, ‘OK, that gives me more impetus to do what we need to do,’ which is double and triple down on increased conservation and efficiency in all sectors.”

He says certain areas, like Tucson, have improved efficiency in the use of water resources compared to recent decades.

Read the full study here.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.