Tall grasses rise from the shallow water at the Ciénega de Santa Clara in Sonora, Mexico.

Tall grasses rise from the shallow water at the Ciénega de Santa Clara in Sonora, Mexico.

CIÉNEGA DE SANTA CLARA, MEXICO — Juan Butrón-Méndez navigates a small metal motorboat through a maze of tall reeds here in the Mexican state of Sonora. It’s nearing sunset, and the sky is turning shades of light blue and purple.

The air smells of wet earth, an unfamiliar scent in the desert.

Butrón-Méndez lives nearby and works for the conservation group Pronatura Noroeste as a bird monitor. (Pronatura’s work receives financial support from the Walton Family Foundation, which also funds KUNC’s Colorado River coverage.)

He cuts the motor in an open stretch of water he calls the “scary lagoon,” ringed by tall grasses that rise from the thigh-high water. Without the boat’s droning hum, coastal birds appear over the reeds, and come in for a water landing.

American coots, with their white bills and dark grey feathers, cackle as they swim. They’re interspersed among broad-winged, yellow-beaked pelicans. Other birds, just silhouettes, dart along the surface, skimming for insects before dark. There’s no sign of them tonight, but several species of threatened or endangered marsh birds — like the Ridgway’s rail — call this place home, too.

VIEW LARGER Juan Butrón-Méndez works for Pronatura Noroeste, a Mexican environmental group, and monitors birds at the Ciénega de Santa Clara.

VIEW LARGER Juan Butrón-Méndez works for Pronatura Noroeste, a Mexican environmental group, and monitors birds at the Ciénega de Santa Clara. Butrón-Méndez has explored this wetland since its creation, watching over the course of decades as the shape-shifting oasis was born.

“Water started to flow to this place in the 1970s. I would walk around here without having to worry about getting wet,” Butrón-Méndez said through a translator. “If there wasn’t water, it’s a dry place.”

He’s been called the Ciénega’s patron saint, able to rattle off its history and the names of the birds, fish and mammals that live here.

The wetland is fed by a concrete canal that removes drainage water from American farms across the border in Arizona. The canal is called the MODE — Main Outlet Drain Extension. The salty runoff inadvertently created this oasis in the middle of the Sonoran desert, a perfect stopover for migratory birds on their journey along the Pacific coast.

“For the birds that migrate from the United States to the south, this is a place of rest, a place for nutrients, to give them strength to continue flying to wherever they’re going,” he said.

VIEW LARGER Sunset at the Ciénega de Santa Clara in northern Mexico. The wetland is fed by salty runoff from American farms near Yuma, Arizona.

VIEW LARGER Sunset at the Ciénega de Santa Clara in northern Mexico. The wetland is fed by salty runoff from American farms near Yuma, Arizona.

But there’s a problem. As the Colorado River basin heats up and dries out like climate projections predict, Butrón-Méndez is concerned people will stop thinking of the water that flows to the wetland as waste, find a way to use it and, in turn, harm the Ciénega.

“The biggest threat that has me thinking, at times,” he said, “although you won’t believe it, I’m thinking that one day when we least expect it the United States will say, ‘No more water for the wetlands of Santa Clara.’”

Geographical, topographical and political boundaries shape the Colorado River’s delta. The U.S-Mexico border bisects the delta, and its fate is controlled by governments, water agencies, farm groups and conservationists on both sides.

Nowhere is that more apparent than at the Ciénega de Santa Clara, one of the delta’s few wetlands, sustained by a water source with an uncertain future.

Wasted water

The Ciénega was born in 1977 when the U.S. began draining salty agricultural runoff to the Santa Clara slough, near the Gulf of California. Years prior, the U.S. agreed not to send degraded water to Mexico, a near-constant tension between the two countries since they signed their first Colorado River treaty in 1944.

In a 1973 agreement called the “Permanent and Definitive Solution to the International Problem of the Salinity of the Colorado River,” President Richard Nixon’s administration agreed to a limit on how salty water would be at when delivered at the U.S.-Mexico border.

To keep the river from becoming loaded with salt, someone had to devise a way to keep the farm runoff from ending up in it. That’s how the MODE canal came to be. After irrigating lettuce fields and date palms in salty soil near Yuma, Arizona, the concrete-lined MODE would take the leftover water across the border close to the Pacific Ocean to dispose of it.

No one meant to create a haven for birds and other wildlife in the dried-out Colorado River delta in the process. But by sending about 100,000 acre-feet of water annually out into the desert, that’s what happened.

VIEW LARGER The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s Yuma Desalting Plant has never been fully operational since it was built in the early 1990s. Filled with obsolete desalination technology, it would require costly upgrades before it could be fired up.

VIEW LARGER The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s Yuma Desalting Plant has never been fully operational since it was built in the early 1990s. Filled with obsolete desalination technology, it would require costly upgrades before it could be fired up. The “Permanent and Definitive Solution” also called for the creation of a treatment facility along the Colorado River that could clean up water from farms along the Gila River in Southern Arizona, within the Wellton-Mohawk Irrigation and Drainage District. Completed in 1992, the Yuma Desalting Plant became that treatment facility dreamed up in the 1970s.

Since it was finished the plant has only run a handful of times, and never at full capacity. It remains in “ready reserve” status and costs upwards of $2 million each year to maintain.

“The Yuma Desalting Plant is nothing but a tool in the toolbox,” said Mike Norris, who manages the plant for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. “It’s a costly tool to operate.”

During prolonged dry spells, though, costly tools become more reasonable. The plant could treat the salty wastewater, send it to Mexico for use on farms and cities to meet treaty obligations, and allow the U.S. to conserve more water on its side of the border, possibly reducing the risk of a shortage declaration in the Colorado River’s Lower Basin.

Water agencies in the state of Arizona, which would be hit hardest with cutbacks in a shortage, have been particularly keen to look at what operation of the desalting plant might look like.

“If we continue in the drought situation, as Lake Mead drops, the plant could be considered as one of the tools to take out of the toolbox to help conserve water in Lake Mead,” Norris said.

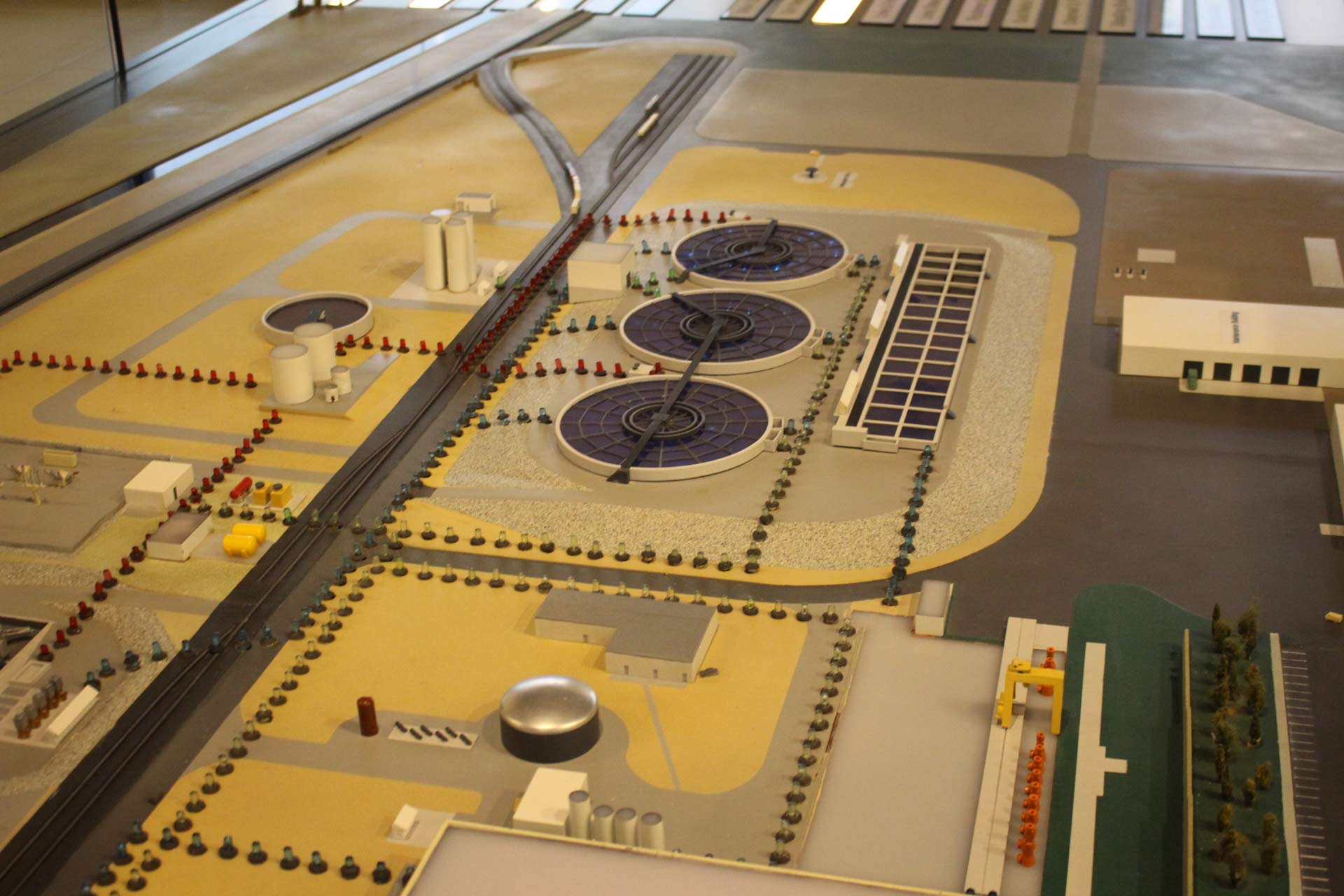

VIEW LARGER A small replica of the Yuma Desalting Plant lights up and illustrates how salty runoff from Arizona farms would be treated.

VIEW LARGER A small replica of the Yuma Desalting Plant lights up and illustrates how salty runoff from Arizona farms would be treated. But it’s not like you can flip a switch and turn this facility on right away.

“There’s a lot of controversy of what that all that looks like,” Norris said. “The big concern is if we ever operate this plant at 100 percent, we’d be directing most of the water into the plant and then what would be going to the Ciénega would be the concentrate water, the higher saline water.”

The Ciénega wouldn’t dry up completely if the plant were to begin operating. Instead, it would receive a greatly diminished amount of water, and what it did receive would be highly saline. The super salty water would likely kill the Ciénega’s cattails and reduce the wetland’s size. It could also see sharp spikes in concentrations of selenium, making it inhospitable to fish and birds.

The wetland does have some protections. The Mexican government has designated the Ciénega as a Biosphere Reserve in the Colorado River Delta. It’s also been recognized for having “great ecological significance” by the Ramsar convention, an intergovernmental treaty on the value of wetlands. If the U.S. were to run the Yuma Desalting Plant it would likely trigger a reconsultation of previous agreements between the two countries.

Because it has sat idle for so long, the Yuma Desalting Plant needs millions of dollars in improvements before it could be fired up, including replacement of aluminum pipes and construction of a chlorine containment facility.

Funds to make those updates aren’t secure.

“We have not been able to get the necessary funds to run the plant at full capacity,” said Maria Ramirez, who oversaw the Yuma Area Office for Reclamation for years. She recently retired. “I don’t know that it will ever run at full capacity,” she said.

Eyes have turned toward the plant this year as states that rely on the Colorado River are finalizing drought contingency plans. Under the Lower Basin’s plan, the federal government committed to conserve 100,000 acre-feet of water a year, roughly the same amount of water currently being sent to the Ciénega.

“Reclamation is looking at all cost-effective means of meeting this commitment,” said Reclamation spokeswoman Patti Aaron in an email.

The delta’s past life

Driving to the Ciénega, it’s hard to imagine what the Colorado River Delta looked like when the river still flowed here. It’s bordered by miles and miles of crusty salt flats. The roads that lead to the wetland become impassable on the rare occasion it rains. They lie on top of layers of sediment — the Grand Canyon’s innards — left here as the Colorado River emptied into the ocean over millions of years.

VIEW LARGER Alejandra Calvo-Fonseca and Juan Butrón-Méndez of Pronatura Noroeste navigate a small boat through the reeds at the Ciénega de Santa Clara.

VIEW LARGER Alejandra Calvo-Fonseca and Juan Butrón-Méndez of Pronatura Noroeste navigate a small boat through the reeds at the Ciénega de Santa Clara. But sitting on a boat inside the Ciénega, you can picture the delta in a past life, full of the green lagoons conservation writer Aldo Leopold described in his 1949 “A Sand County Almanac.” He explored the Colorado River Delta by canoe with his brother in 1922, nearly a decade before construction began on Hoover Dam.

The picture Leopold painted of the Colorado River Delta is a sensory experience. Gambel quails whistle. Raccoons munch. Jaguars sneak. Waters radiate an emerald green.

“When a troop of egrets settled on a far green willow,” Leopold wrote, “they looked like a premature snowstorm.”

Juan Butrón-Méndez said the only way to prevent the Ciénega from being harmed is for more people to know about it. One big threat, he said, is simply ignorance about its existence. If no one knows about the wetland’s value, they wouldn’t be upset if it disappeared, his thinking goes.

During our interview, he extends a standing invitation to visit any time and get lost among the cattails.

Still, he knows about the outside pressures that weigh on the Ciénega — like climate change, growing populations, and tension between the U.S. and Mexico over immigration and trade — leaving its fate uncertain.

“The two countries, we’re neighbors, right? The United States and Mexico,” Butrón-Méndez said. “Well, we need to have an agreement between the two countries, right, that [removing the water] wouldn’t happen. Because it would be a disaster.”

This story is part of a series on the Colorado River delta, and part of an ongoing project covering the Colorado River watershed, produced by KUNC and supported through a Walton Family Foundation grant. KUNC is solely responsible for its editorial content.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.