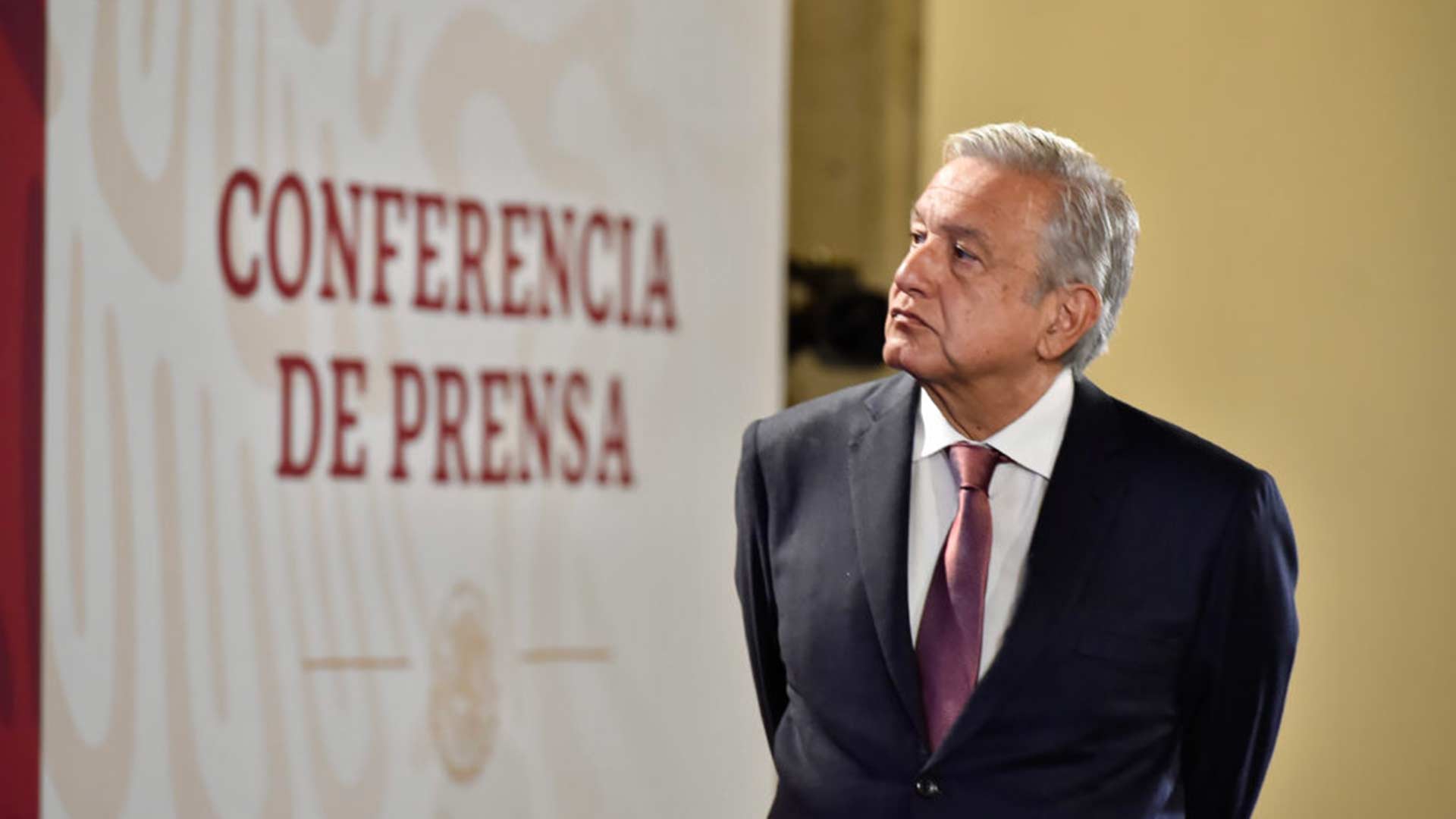

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador at one of his press conferences at Mexico's National Palace in Mexico City.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador at one of his press conferences at Mexico's National Palace in Mexico City.

MEXICO CITY — In Mexico, the president tends to admonish certain journalists — in a way, like the president in the United States. And just like in the United States, social media in Mexico has become a key player in the confrontations between the state and the press.

Tensions between the press and the government in Mexico have arisen, as President Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) uses derogatory expressions condemning some journalists and media outlets — expressions that have become viral.

Crossing the Line?

President López Obrador likes to offer early — and daily — press conferences at Mexico’s National Palace in Mexico City. During a recent one, he was confronted by Jorge Ramos, the same journalist that clashed with President Donald Trump in 2015.

Days before, Mexico’s Reforma newspaper published a filtered letter from AMLO. The president disdained the publication and suggested that Reforma, or anyone with privileged information, should make its sources public.

“Don’t you think that asking journalists to reveal their sources is an attack on the press?” Ramos asked AMLO.

“No, no, it’s not an attack,” replied the president. “Do you know why I said it? Because I want to exercise my right to reply.”

“And we [journalists] want to use our right to express freely,” Ramos retorted.

AMLO has lifted some restrictions to the press — for example, with these conferences — but he ridicules and uses derogatory terms against journalists and media outlets that question him. Reforma has been demonized by AMLO just like the New York Times by Trump.

“You [journalists] are prudent here because you know they’re watching you, because you know what will happen to you if you cross the line, and not because of me, but because the people are watching,” AMLO told to journalists at a recent press conference.

Other elected officials from his party, Morena, are replicating his attitudes toward the press. For instance, Laura Beristáin, a mayor in the state of Quintana Roo, accused journalists of being “sicarios” (hit men) for publishing stories about violence in the region.

License to Attack

“Ninety-nine percent of violent actions against journalists are left unpunished in Mexico, and 50 percent of aggressions to the press come from public officials,” said Leopoldo Maldonado, regional director for Article 19, an international freedom of information organization.

The activist says the press ended up badly beaten by the previous administration of Enrique Peña Nieto, and López Obrador brought a light of hope. But his government needs to act fast to stop the violence against journalists, while discontinuing its abusive language.

VIEW LARGER Leopoldo Maldonado is regional director in Mexico for Article 19, an international freedom of information organization.

VIEW LARGER Leopoldo Maldonado is regional director in Mexico for Article 19, an international freedom of information organization. “The accusations and name-calling coming from the head of the state, disqualifying and mocking the press, license aggressions from others toward journalists,” Maldonado said.

The Mexico chapter has pronounced repeatedly against AMLO's rhetoric, asking him to "refrain from generating any act that inhibits the exercise of freedom of expression and that may put life, liberty, integrity and security from journalists at greater risk."

More recently, the organization urged president López Obrador's administration to protect Reforma's publisher after being the victim of death threats and attacks online as a result of AMLO's incendiary criticism against the publication.

‘Preppy Press’ and ‘Sellouts’

Many are already suffering consequences and impact of AMLO’s rhetoric. Among them is Ivonne Melgar, a journalist and columnist who has been targeted on social media after questioning AMLO. The language used against her echoes the president.

“They have accused me of licking the boots of former presidents, of being part of what the president calls ‘prensa fifí’ (‘preppy press’), of being a ‘chayotera’ (Mexican slang for a sellout journalist), a conservative traitor and a two-faced hypocrite,” Melgar recalled.

VIEW LARGER Ivonne Melgar is a journalist and columnist based in Mexico City.

VIEW LARGER Ivonne Melgar is a journalist and columnist based in Mexico City. Melgar describes the serial messages as a machinery ready to assault.

“The so-called YouTubers and users in social media begin to use the terms, the language, the behavior patterns that come from those in power, because the president's narrative is very powerful and has a lot of credibility in sectors that are perhaps less informed,” Melgar said.

This social media behavior was studied at Signa Lab, a research center from the Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Occidente (ITESO) university in Guadalajara. They found a series of coordinated and viral attacks led by unidentified AMLO followers.

VIEW LARGER Signa Lab is a social sciences research center focused on new technologies, at the Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Occidente (ITESO) university in Guadalajara.

VIEW LARGER Signa Lab is a social sciences research center focused on new technologies, at the Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Occidente (ITESO) university in Guadalajara. “To disqualify your work by creating a narrative that labels you and others like you, in physical terms, puts you on target,” said Melgar.

Melgar considers AMLO a charismatic, seductive and even affectionate character. And she recalls previous administrations using bribery or coercion to suppress freedom of speech.

“Everything was done in the dark before, like phone calls to your supervisors or pressure asking you not handle certain stories, but now it's a frontal attack from the presidency, although his message might be more directed towards the owners of the media outlets,” said Melgar.

The journalist is worried about the impact that the president’s rhetoric may have in her already endangered profession.

“Our jobs, reputation and safety as journalists are more vulnerable now,” said Melgar.

Both Melgar and Maldonado from Article 19 think those who endure the confrontations will become a better counterweight to the state.

“There will be some sort of Darwinism among those who can stand the confrontation. The media with a true calling for journalism will have to break with the perverse business model with the state that existed before,” said Melgar.

“The journalistic guild is going to have to talk more to their audiences than to the powerful,” said Maldonado.

But at Mexico’s National Palace, López Obrador insists on calling names to the press, defending his right of reply.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.