Protester Ana Paula Contreras collects donations from drivers at a toll booth outside Magdalena, Sonora, on the highway that connects Nogales and the capital city of Hermosillo.

Protester Ana Paula Contreras collects donations from drivers at a toll booth outside Magdalena, Sonora, on the highway that connects Nogales and the capital city of Hermosillo.

“It’s free! It’s free! You guys can pass.”

Ana Paula Contreras waved a car with Utah plates though a toll booth near the little town of Magdalena, Sonora. It’s about 60 miles south of the Arizona border on Sonora’s Highway 15, a route familiar to tourists bound for Sonoran beach towns like Kino Bay or San Carlos.

Protesters like Contreras have been shutting down, or liberando, Sonoran toll booths like this one for nearly 10 months now.

“We want everybody to know why we’re right here,” she said.

But many U.S. travelers have no idea.

“Can you tell us what’s going on?” Cary Carlson asked after I waved him and his wife Kathy down as they passed through the Magdalena toll booth on their way to San Carlos on a recent Friday afternoon.

Lights above the booth glowed with big, red X's, and faded orange jersey barriers blocked traffic through all but one lane. The protesters ushered people through the open lane, holding out plastic jars for drivers to toss donations into.

The couple from Washington state said they’re used to seeing protesters on their drive through Sonora, but they usually have no idea what they’re protesting.

“Sometimes they have signs,” Carlson said. “These guys don’t really even have signs that I can see.”

Free Transit

VIEW LARGER An Arizona driver passes through the toll booth near Magdalena, Sonora.

VIEW LARGER An Arizona driver passes through the toll booth near Magdalena, Sonora.

Toll booth protests are common in Sonora and across Mexico to bring attention to all kinds of causes, from high gas prices to insecurity to education reform.

Since July, demonstrators in Sonora have been taking over the casetas de cobro to push back against the tolls themselves.

“We’re not going to pay anything,” Miriam Murrieta and Martín Delgado said in unison.

They’re leaders with the he Movimiento Libre Tránsito Sonora, or the Sonoran Free Transit movement, at another toll booth just north of the Sonoran capital city Hermosillo.

“It should be free, or free transit,” Murrieta said.

“Because that’s what the constitution says,” Delgado said.

They want to get rid of toll booths all together in the state of Sonora because charging tolls doesn’t match up with their interpretation of the Mexican constitution, which guarantees free of movement of people within Mexico.

“It’s an abuse of those who have the least,” Delgado said.

A few bucks might not seem like much to beach-bound tourists, but the cost falls hardest on those who live near the tolls, often in rural areas. For people who live outside of Hermosillo, just entering and exiting the city costs almost $10 round-trip, or nearly twice Mexico’s daily minimum wage.

“It’s hitting us in the pocketbook,” Delgado said.

Staying Put

VIEW LARGER A sign at the toll booth near Magdalena, Sonora, tells drivers they can pass without paying.

VIEW LARGER A sign at the toll booth near Magdalena, Sonora, tells drivers they can pass without paying. The Sonoran protests started as an appeal to then-candidate and now President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO). Many see him as a champion of the people. But his administration hasn’t been quick to respond to protesters’ demands. And as the protests wear on, they’re costing the government millions.

In the first six months, the Sonoran protests cost more than more than $30 million in lost toll revenues, according to data obtained by KJZZ. Several government officials declined to be interviewed for this story.

Workers still sit in the toll booths everyday during the protests to take money and hand out receipts to anyone who wants to pay. There aren’t very many, Murrieta said.

Instead, the protesters shake plastic containers asking for donations. They said they’re using the money for supplies like food and water at the toll booths, and they’re donating the rest to members of the community.

That irks some Sonorans, including both some travelers and business owners, who believe the protests are cutting into funds that should go to improving roads and keeping drivers safe. People who don’t want to pay the fee can use alternate routes, they said.

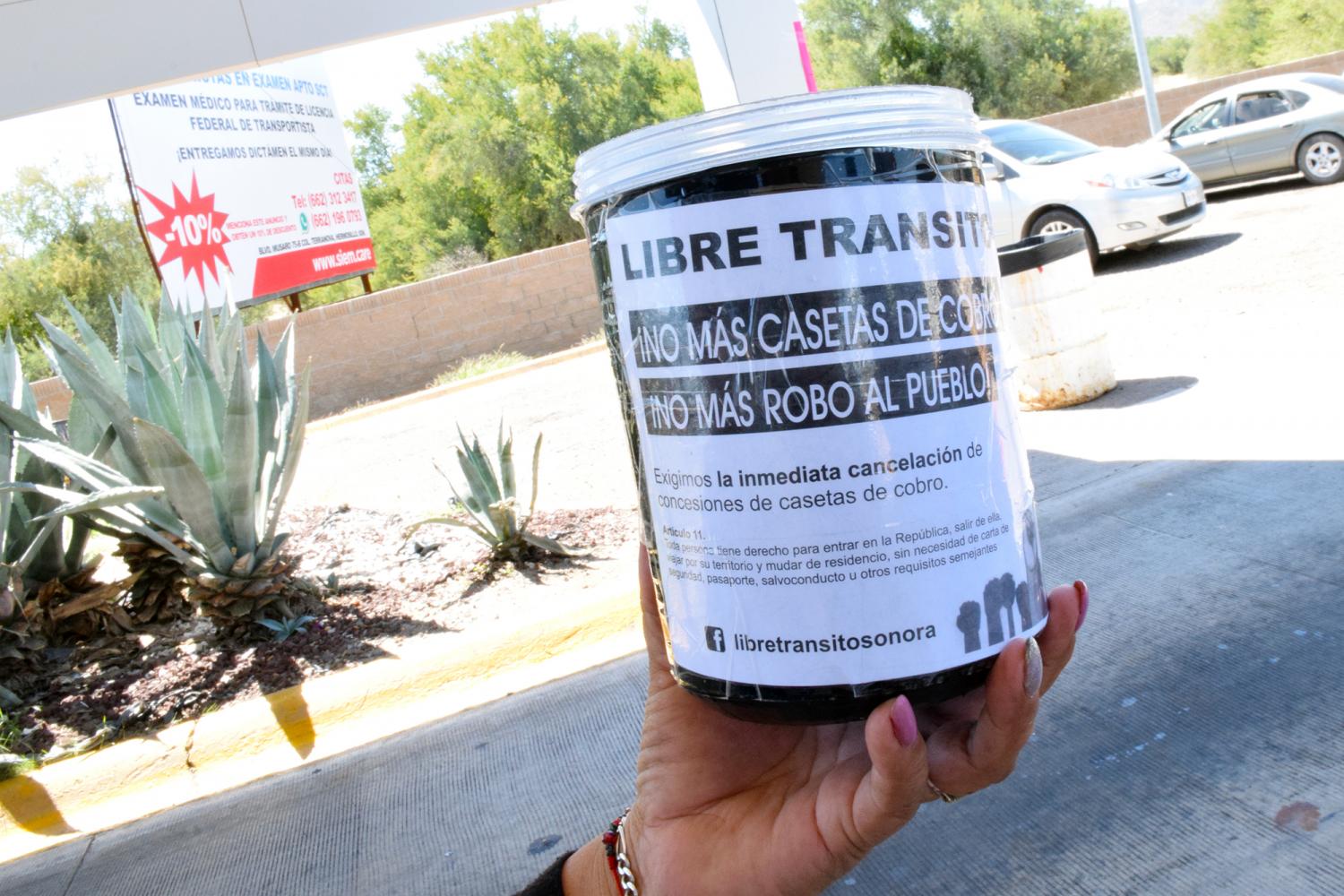

VIEW LARGER Protesters have taped a flyer about their movement to a can they use to collect donations from drivers.

VIEW LARGER Protesters have taped a flyer about their movement to a can they use to collect donations from drivers. But supporters of the movement disagree. They don’t want to pay the hefty toll costs, and some doubt that money ends up going where it's supposed to anyway.

“We’re in favor of the protesters taking over the toll booths,” said Javier Leon.

He was traveling with his family south from the border town of Nogales, Sonora to Obregón, in the south. He said he’ll hit four or five toll booths on the way. The cost really adds up. He said he hopes the protesters get their way.

Delgado thinks they will.

He’s been to Mexico City to meet with government leaders twice this year. They’re working on a compromise that would give Sonoran residents a free pass through the toll booths.

“That’s what we’re fighting for, for those who really use the highway, the residents, so that they’ll give them a sticker so they can pass through the toll booths,” Delgado said.

But the Mexican Transportation Secretary Javier Jiménez Espriú said during a recent visit to Sonora that he had no plans to stop collecting tolls.

Either way, protesters won’t be going anywhere until something changes, Murrieta said.

“We’re going to be here insisting, pushing, until we achieve our goal,” she said.

Come rain, shine or scorching summer days, the protesters will be there, Delgado agreed.

“Hot weather is coming, but we’re here,” he said. “We have to keep pushing forward until they solve this.”

VIEW LARGER A protester collects donations at a toll booth outside Magdalena, Sonora, April 2019.

VIEW LARGER A protester collects donations at a toll booth outside Magdalena, Sonora, April 2019. In Magdalena, Contreras said protesters are staying put too.

“It’s the same thing. Nothing has changed,” she said. “Until we see that they aren't charging anymore, we’re not leaving.”

As for travelers, they should just go with the flow, said Jhan Lampkin, who was heading south from Green Valley to her home San Carlos with her dog.

“I just keep some change handy and throw it in the bucket for them and hope for the best,” she said. “They wish me a ‘buen día,’ and I wish them a ‘buen día.’”

Besides, she added, it’s nice not having to pay the tolls.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.