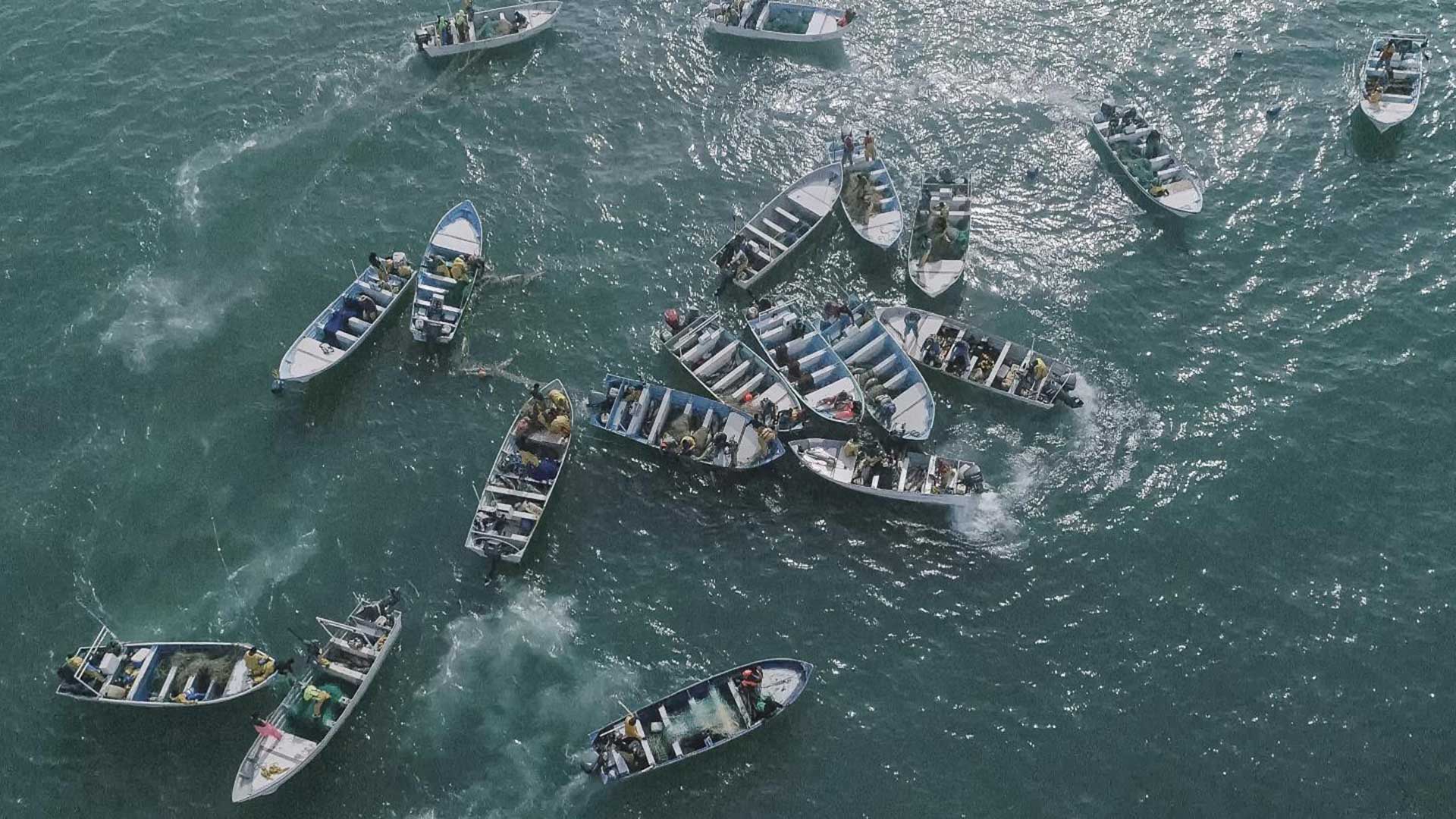

More than 80 small fishing boats illegally cast nets into the Sea of Cortez in an area inhabited by the vaquita marina porpoise on Dec. 8, 2019.

More than 80 small fishing boats illegally cast nets into the Sea of Cortez in an area inhabited by the vaquita marina porpoise on Dec. 8, 2019.

Activists in Mexico’s Sea of Cortez say poachers are overwhelming a refuge area meant to protect a nearly extinct porpoise. And they’re using new fishing techniques to avoid having their nets confiscated by authorities.

On Sunday, more than 80 small fishing boats filled with hundreds of fishermen swarmed an area of the Sea of Cortez known to be inhabited by the vaquita marina porpoise — the world’s smallest and most endangered marine mammal — according to Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, which removing illegal fishing nets in Mexico's Sea of Cortez since 2015.

Poachers cast large nets in the area, hoping to catch a huge fish called the totoaba. It's a protected species, but often poached in this area because its swim bladder is valuable on the black market in China.

VIEW LARGER Hundreds of poachers illegally caught totoaba in a refuge area for the nearly extinct vaquita marina porpoise on Dec. 8, 2019.

VIEW LARGER Hundreds of poachers illegally caught totoaba in a refuge area for the nearly extinct vaquita marina porpoise on Dec. 8, 2019. During the winter, totoaba migrate north to the vaquita’s refuge near San Felipe, Baja California, putting the small porpoise at risk. Vaquitas are ensnared and drowned in the large nets used to catch totoaba. The nets are considered the principal threat to the small porpoise, which is nearly extinct with only an estimated 10 left.

Fishing in this area has been prohibited for years.

While it's not unusual to see a surge in poaching in the winter months, Sea Shepherd's Captain Locky MacLean said the number of poachers openly casting their nets in recent days is unprecedented.

“This is the most blatant act of poaching that we’ve seen in all of our years in the Sea of Cortez," he said, adding that poachers have also changed their tactics.

In the past, poachers set their nets and came back to retrieve them hours later. Earlier this year, attempting to escape detection, MacLean said some poachers were removing floats that keep the nets near the surface. But Sea Shepherd easily spotted those using sonar.

VIEW LARGER Sea Shepherd crew pull totoaba out of illegal fishing nets

VIEW LARGER Sea Shepherd crew pull totoaba out of illegal fishing nets Now, some poachers are using a method called "pesquería de encierro," using multiple nets to encircle and trap the totoaba. In some cases, poachers pull in the nets, immediately cut open live fish to remove the swim bladder and tossed the bodies back into the water, MacLean said. The poachers also used their large numbers — at least 80 boats and upwards of 400 fishermen — to overwhelm the few authorities in the area.

“We saw a free for all over the last few days, a complete free-for-all," he said. “I think this whole thing has been a wake-up call for the authorities, and we will be looking forward to more of a presence in the area."

"I see it as a very complicated situation," said Lorenzo Garcia, leader of the largest fishermen's federation in San Felipe. He's helped lead an effort to push the government to address illegal poaching in a way that doesn't hurt legal fishermen in the uppermost part of the Sea of Cortez.

For years, fishermen in the area were a paid a compensation not to fish in the vaquita's habitat. But due to budget cuts, the Mexican government stopped paying fishermen last December, so many returned to the water, arguing they couldn't support their families with neither work nor financial support from the government. However, they promised to avoid the most critical area of the vaquita refuge.

"We're respecting the refuge zone, as we've always said," Garcia said. "But we see people coming in from other places and they're doing whatever they want, in the light of day."

Garcia blames a lack enforcement for brazen poaching in the area.

During its annual meeting August, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) also made strong recommendations that Mexico increase enforcement efforts in the region. Though the group did not impose sanctions on Mexico, as some conservationists had hoped.

"It's difficult," MacLean said. "There are other underlying problems in the area. There are socioeconomic problems, and one of the main things is the continued trade with China as far as the black market as far as totoaba bladders."

He said he believes Mexico is working to cut off buyers who traffic the swim bladders to China and said it's a critical moment to address the issue from all sides.

"We’re looking forward to seeing action," he said. "Especially now as the season gets higher and the risk for the vaquita gets greater and greater over December and January."

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.