Insects spend a lot of time upside-down and sideways, but scientists know surprisingly little about how their bodily fluids handle the pull of gravity in these awkward positions.

Now, a studyin the journal PNAS sheds new light on the topic.

An insect's open circulatory system, which sloshes fluid around a cavity instead of pumping it through blood vessels, should make it more vulnerable to gravity's tug.

"That was something I've kind of always wondered, but never had any way to study it," said lead author Jon Harrison of Arizona State University's School of Life Science.

But when Harrison and colleagues observed fluid flow in the American grasshopper (Schistocerca Americana), a grasshopper commonly used in research, they began to question this simple picture.

"We started flipping them upside down, right-side up and really being able to just see — in real time, in front of us — the effect of the blood moving and compressing whatever part of the grasshopper was down," Harrison said.

X-ray imaging and radioactive tracing revealed evidence of internal valves that help maintain fluid pressure in parts of the grasshopper's body.

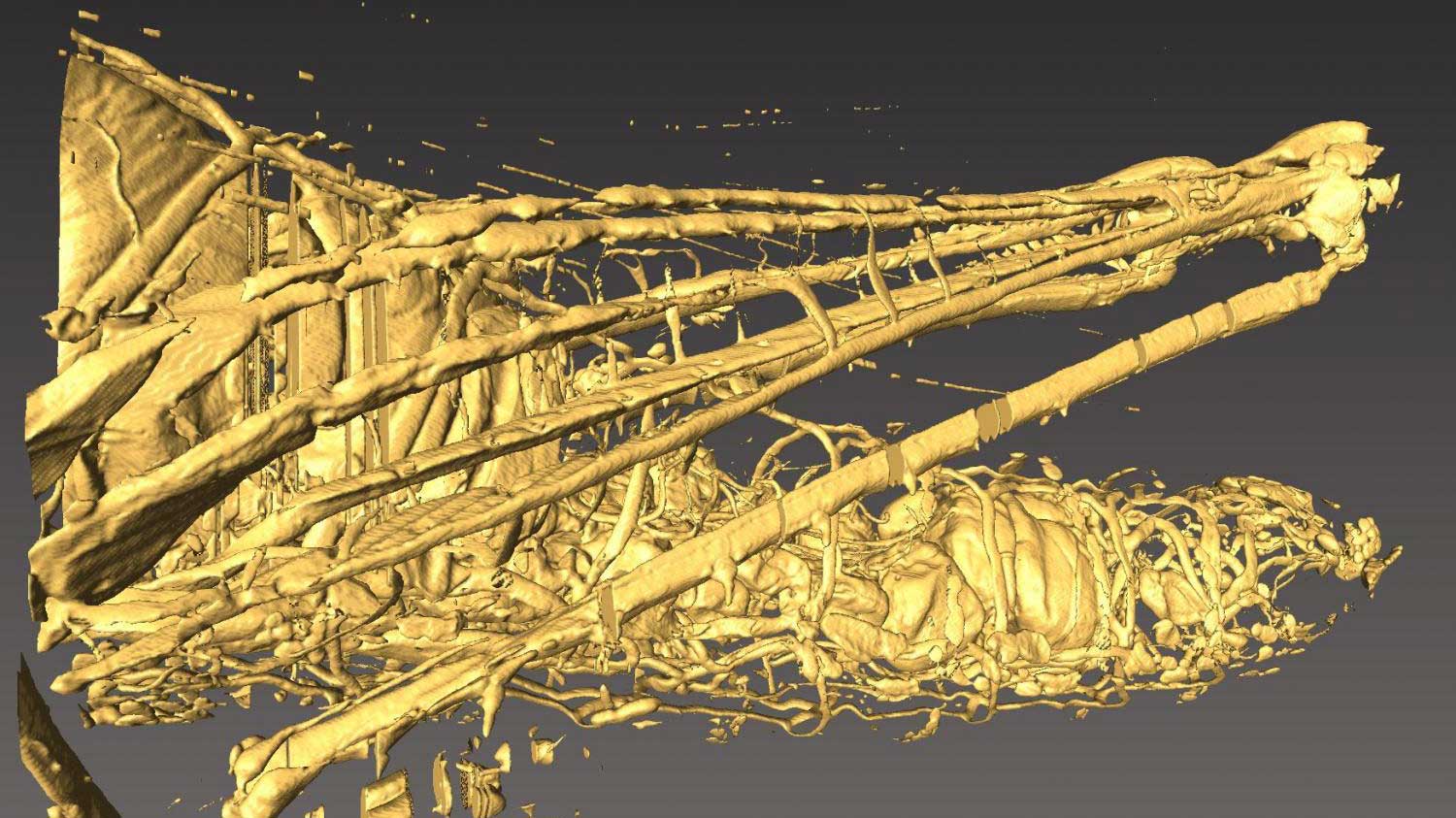

VIEW LARGER A 3-D microtomographic image of a grasshopper in a head-down position. The inflated air sacs in the abdomen are visible. The tomography was performed at Virginia Tech.

VIEW LARGER A 3-D microtomographic image of a grasshopper in a head-down position. The inflated air sacs in the abdomen are visible. The tomography was performed at Virginia Tech. "The fact that we can measure different pressures that aren't coincident in different parts of the grasshopper tells us that there has to be some kind of functional valving, even though people haven't been able to go in and find it," Harrison said.

Although the fluid in question, called hemolymph, is a bit player in distributing oxygen in a grasshopper's body – a task handled by a network of air sacs and tubes — it does provide vital water, ions, nutrients and hormones to tissues.

The researchers also found that grasshopper's heart rates sped up and slowed down in response to body position, much like vertebrates.

The findings could have important implications for molecular biology, which makes wide use of the insects as lab models of biological processes.

But researchers also suspect the systems they've observed in grasshoppers might occur widely in invertebrates. If so, the possibility that gravity responses to might evolve early in cardiovascular systems and exist across a wide array of animals could also have notable repercussions for evolutionary biology.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.