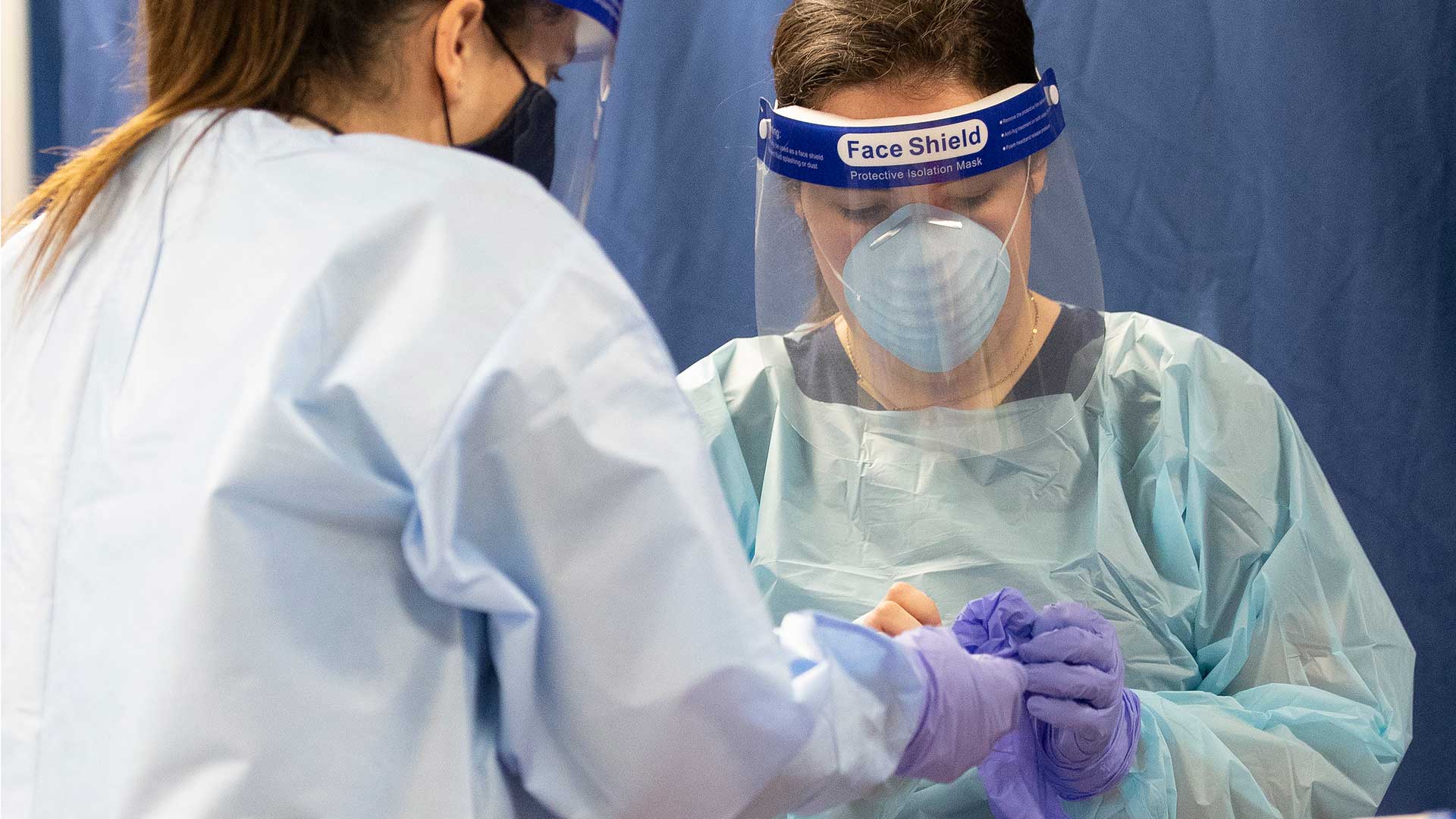

Pima County COVID-19 testing at the Kino Events Center, July 13.

Pima County COVID-19 testing at the Kino Events Center, July 13.

Arizona has topped headlines and lists in recent weeks for its surging case and hospitalization numbers and a percent positive test rate that showed the spread of the novel coronavirus was well beyond the state's capacity to test and track.

Certain metrics show signs of leveling or ticking down, for now, but Dr. Kacey Ernst, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Arizona, says there is a lot of work to do to put Arizona on track to contain the disease.

Nick O'Gara spoke with Ernst on July 14 about testing, contact tracing and why people might take risks. Find an edited version of the interview below.

'Chapter 1'

AZPM: At one point people warned of a sort of second wave of the coronavirus, and then eventually some people started to say places like Arizona are still in the first wave. The talk of vaccines varies but the earliest are still many months off. Can you locate us in Arizona, in Tucson, in the progression of the pandemic? What chapter are we in in this narrative?

ERNST: So I think we're still in Chapter 1. I think that what we saw in sort of March and April may have been considered a prologue, and now we haven't really gone into what I would consider a second wave. That is probably going to occur more in the fall or late fall. So, that is sort of the status where I think we are.

I would be very hopeful that we're going to see a downturn that would actually allow us to distinguish it as a different wave, but we're still pretty early on in our transmission of this new virus.

'If we had really good testing...'

So recently there were a few changes in Arizona restrictions. On June 17 mayors were allowed to implement mask policies. On [June 29] the governor shut down bars, gyms and movie theaters. How long does it actually take to see the changes that changes like that might bring? Is it 10 days, is that enough? Is it two weeks?

If we had really good testing it wouldn't take us long for us to see what was going on. Right now, when you have testing lags of seven to 14 days, and in many locations you're actually not even able to see what happened, you know, a week ago because you're still waiting for results ... so all of those things sort of compound.

My guess is, typically without testing delays you would probably start to see some changes or some flattening after about two weeks or so. And now I think just given all of the testing issues it's going to be a bit longer than that — probably at least another another week or two. And it depends on what metric you're thinking about, right, so it depends on if you're talking about positive tests, or hospitalizations, or deaths.

The first thing that ramps up, of course, is the positive tests in cases. Then it's the hospitalizations and then it's the deaths, because of that sort of lag between when you first get infected and how long it takes before you might need to be hospitalized. And then once you have that severe illness, it may take a while longer for you to succumb to the disease.

So all of those kind of have a different sort of duration at which you would see a shift occurring due to our interventions.

Not about the numbers, it's about the speed

The governor has put a few numbers on the goals of testing in his most recent briefing ... 35,000 tests per day by the end of July, and I think 60,000 tests per day by the end of August. Where do we need to be to start getting it under control or being able to understand what we are seeing?

So I think absolute numbers of tests is not the goal. I think the goal is, if you are symptomatic, if you have been exposed to somebody who has a confirmed case of COVID, you can easily and readily access a test and that you actually get a turnaround time that's within, you know a three-day window, because what we need is we need testing to be really efficient and rapid so that we can launch a case investigation and contact tracing, and we can quarantine people who have been exposed in order to prevent further transmission.

So, those are the metrics I would look at. I would not look at absolute number of tests. I don't think that that's a very meaningful metric at all.

Contact tracing

What other kinds of gaps are we seeing in terms of the ability to track the spread in Arizona?

So I think just there's there's so many cases right now, and the delays in getting that information — even if we had all of the contact people ready to start tracing, what they would have to do is basically truncate, and say, "OK, any cases that we haven't investigated that are more than a week old, we're just going to have to cut our losses and really go with the current, new cases that are coming in." Because those are the ones that you can really effectively go after to try and prevent further transmission in their contacts.

I think you absolutely want to go back and do those case investigations later on, but really focusing on the ones that can make a difference in sort of ongoing transmission is really critical.

So that's certainly one thing, you know, the contact tracing ... capacity is still being built. I think it's going to ramp up relatively quickly, now there's a lot of new contracts in place, etc., so my hope is that we will start seeing that sort of go down.

But of course we also have to have people answering their phones. People need to be on board with talking to public health about this, and be willing to go ahead and provide information on contacts. And it should be noted that this is not something new. Contact tracing is something we've done for ages, and it's our best strategy to really contain diseases that don't have a cure and don't have sort of an immediate prevention, especially with respiratory infections.

So I think that's you know that's one of our primary strategies. One of the things that I want people to know is that — we're helping here at UA, NAU is helping, ASU is helping out with contact tracing. And so if you see a phone number that's unknown but it says "university," or "health department," or something like that, it's important to be able to pick up that phone and provide people with the information that they may need.

Why people take risks

People have linked the surge we're in now to younger age groups, so I guess my question is, how are public health professionals talking about why people are or have been taking risks even though they know there's a pandemic? So it's sort of two questions for me. What are the ingredients from a public health perspective that lead to buy-in from the community to not take risks, and also, how do you convince younger people of the risks in their actions?

I think, of course, you know there's a lot of models out there about health behavior, and some of the components that are included are things like your perception of risk. So, do you perceive that you are at risk of both infection as well as severe consequences of the infection? That's sort of a top layer. Also, behavioral and social norms that you see around you. So, if your peers are saying, 'Hey it's fine, let's go out to the bar." You may be more likely to go along with it than if you have this sort of more cultural and social norm of taking more precautions.

It's understandable in many ways. I mean, we were under this sort of stay-home order, and then we were released from this stay-home order, which I think gave people this sort of false sense of security, where when we closed down, we were at lower case numbers. Then when we sort of opened things back up again, I think people equated that openness with being safe to go about their normal daily routine.

And they did hear the messages about, you know, well, it's immunocompromised and it's older people who are at risk, and a lot of people look at that sort of death metric, but we have to keep in mind that that's not the only negative outcome with this virus, that it is also leading to hospitalizations. It's leading to increases in stroke, and even if you are young and healthy you're not invulnerable. There is still risk even if it is lower than if you're, you know, 75 with a chronic health condition.

There are still serious risks to getting this infection when you have 15-20% of people being hospitalized. That's a very, very large number of people.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.