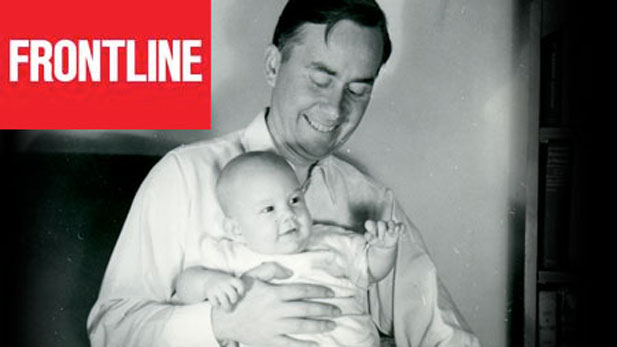

David Iverson with his father, Bill, in Palo Alto, California, in 1949.

Beginning with the story of his own Parkinson’s diagnosis several years ago, correspondent Dave Iverson sets out on a personal journey to understand a disease that scientists believe could hold the key to unlocking the secrets of the rest of the major brain diseases that afflict millions each year.

Along the way, he meets some remarkable people — a leading Parkinson’s researcher whose encounter with “frozen” heroin addicts led to a major breakthrough; a Parkinson’s sufferer given a new lease on life by an experimental brain surgery; and a geneticist who helped identify some of the gene mutations responsible for Parkinson’s and who is now working on drugs to fix them.

Iverson also has intimate conversations with fellow Parkinson’s sufferers actor Michael J. Fox and writer Michael Kinsley, who describe how they became caught up in the politics of Parkinson’s research after the Bush administration greatly restricted federal funding for promising stem cell research in 2001, three years before Iverson got his diagnosis.

“When you’re talking about the potential to heal and cure and it’s not going forward because of its value as a political wedge issue,” Fox says of his reaction to the Bush stem cell restrictions, “it pissed me off, and I wanted to do something.”

Until recently, genetics was thought to play no real role in Parkinson’s disease at all, but Iverson’s family history leads him to enroll in a genetic study at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida. To date, researchers have identified at least six genes where mutations can cause Parkinson’s, and while the familial form of the disease remains unusual, it may provide researchers with a ready-made target to fix the genes. “We’re a lot closer than we were 10 years ago,” says Mayo Clinic geneticist Matthew Farrer, “a lot closer.”

Finding a cure for Parkinson’s disease may still be on the distant horizon, but in the interim, millions of Americans find ways to live with the condition. Iverson examines one of the experimental surgical interventions that attempts to compensate for the lack of dopamine that characterizes Parkinson’s: a fetal brain cell transplant. “Now we talk about the concept of brain repair,” says surgeon Dr. Ivar Mendez. “Brain repair, when I was in medical school, was not even something that was thought about. So we have advanced tremendously over these years to be able to understand there’s the possibility that we can potentially repair the brain.” While some forms of fetal cell transplant surgery appear to have yielded positive results, others have proved disappointing, in some cases even making patients worse. Dr. Bill Langston of the Parkinson’s Institute tells Iverson: “There’s an old saying in science that research is the process of going up alleys to see if they’re blind. And more often than not they are. But that’s what we do.”

Toward the end of the film, Iverson finds a new source of hope in a very unlikely place: new research that indicates that regular exercise may help delay or slow down the progression of Parkinson’s. Says one leading researcher: “It’s not at all hard for me to imagine that the results of a properly designed exercise program are going to be more effective than many of the medications and surgeries we have now.”

FRONTLINE’s Web site will feature a live online discussion about Parkinson’s disease with correspondent Dave Iverson immediately following the broadcast of “My Father, My Brother and Me”; live discussion begins at 10:00 p.m. ET.

Dave Iverson and University of Arizona Parkinson's researcher, Scott Sherman, MD, PhD, will speak in Tucson on March 3rd at the Power over Parkinson's Conference in Tucson.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.