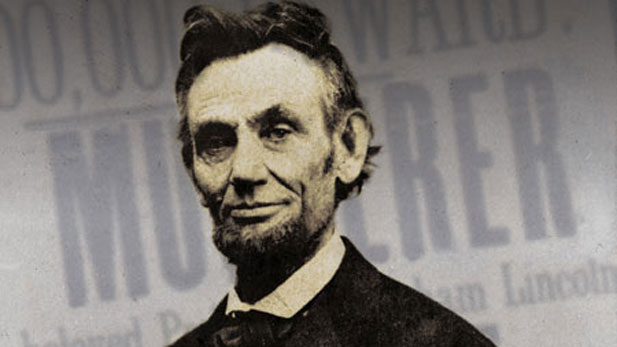

In November 1860, a little-known Republican state senator from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln was elected president of the United States. A vocal opponent of slavery, Lincoln’s victory enraged millions of Southern sympathizers, including an acclaimed young actor named John Booth, who blamed abolitionists for the growing division of the country.

“You all feel the fire now raging in the nation’s heart. It is a fire lighted and fanned by Northern fanaticism, a fire which naught but blood can extinguish,” Booth wrote in a monologue he would never deliver.

By 1862, the small skirmish that began the previous year had turned into a full-blown civil war, a bloody stalemate with no end in sight. As casualties stumbled into Washington, Lincoln haunted the War Department, absorbing the loss of life all around him. Out of all the suffering, he resolved, must come what he would later call a “new birth of freedom.”

In January 1863, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, an order freeing the slaves within the Confederate states and transforming the meaning of the Civil War. By August 1864, a second presidential term seemed improbable, until the Union army broke through Confederate defenses in Atlanta, Georgia. It was a victory that allowed Lincoln to win a second term.

For Booth, the news of four more years of Lincoln as president was almost too much to bear. At 25 years old, his dreams of glory beyond the stage were passing him by.

On April 3, 1865, the Confederate capital in Richmond, Virginia, fell to Union forces. Only six days later, General Robert E. Lee surrendered and the war was effectively over. Booth was overcome with disappointment and bitterness. He resolved to punish the North for what it had done to the South, and his desperation gave rise to a new scheme: to kill the tyrant responsible for the demise of his beloved Confederacy — Abraham Lincoln.

The AMERICAN EXPERIENCE Web site pbs.org/amex provides students, educators and lifelong learners with an ever-growing library of free and trusted American history resources.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.