The stinknet weed (Oncosiphon pilulifer), seen here with a key for scale, was being traded as Globe chamomile before being renamed. Scientists say it is an invasive plant in our region.

The stinknet weed (Oncosiphon pilulifer), seen here with a key for scale, was being traded as Globe chamomile before being renamed. Scientists say it is an invasive plant in our region.

The Buzz for April 12, 2024

The problem of invasive plant species in southern Arizona is not new.

From early ranchers and miners who brought plants that they thought would make their work easier to recent population booms, where people brought their favorite decorative plants as they relocated to warmer climates.

Those non-native plants all have the ability to leave the confines where humans hoped to keep them and move into natural ecosystems.

And some have.

"Buffelgrass was brought in for erosion controlling grazing as agriculture was booming. About 100 years ago, the [19]20s and 30s," said Ben Tully, an invasive species outreach educator with the University of Arizona Cooperative Extension. "The USDA found this wonder grass, buffelgrass, in Africa and thought, 'oh, that helped with stabilizing the soil and farms and mines as well as feeding the cattle.' And they did not think about the repercussions, did not think about how it would outcompete natives and it being flammable."

VIEW LARGER A bunch of buffelgrass after it was sprayed with the blue-tinted herbicide in Saguaro National Park August 2021.

VIEW LARGER A bunch of buffelgrass after it was sprayed with the blue-tinted herbicide in Saguaro National Park August 2021. Buffelgrass and the related plant fountain grass are both perennial bunchgrasses that can crowd out spaces in which native plants would normally thrive.

"It grows in this big bunch and perennial means is long lived, it lives year after year," said Frankie Foley, a biologist at Saguaro National Park. "There are other non-native perennial bunchgrasses that are in the park and in the forest and public lands all around us and in town as well. They don't tend to have the biomass that buffelgrass does have. There's another species called fountain grass that does have that biomass, a lot of fuel above ground. Fountain grass is an ornamental plant unfortunately, so it's really pretty and that's been to our detriment here in the park. It has done a wonderful job of filling in drainages."

Filling in those drainages gives it first access to the water that comes through, using up a precious resource before it gets to native plants.

Then there is the newest invasive plant to arrive.

"Stinknet's [arrival] is unknown. It was like a stowaway on a boat or something," said Tully. "It was first seen in California. So it could have been on some equipment, someone's clothes, anything but it was definitely not intentional for stinknet.

"It actually did used to have a different common name called globe chamomile, and that sounds really lovely," said Foley. "We needed to do a rebranding effort on that one, because we did not want people to think that it was a welcome species."

They said stinknet's new name is fitting due to its smell and other issues.

"There was a fire in 2020 called that Aguila Fire. That fire was carried largely by stinknet," Foley said. "And speaking with wildland firefighters that were on that fire the they reported that the smoke was just so toxic and caustic that it really gave them respiratory problems. And that is something that we're seeing in populations that are living in or near stinknet is people are dermatitis or skin irritation. I personally my nose starts running like crazy when I'm pulling it. People get headaches really easily and have respiratory problems as well. It's really a nasty plant."

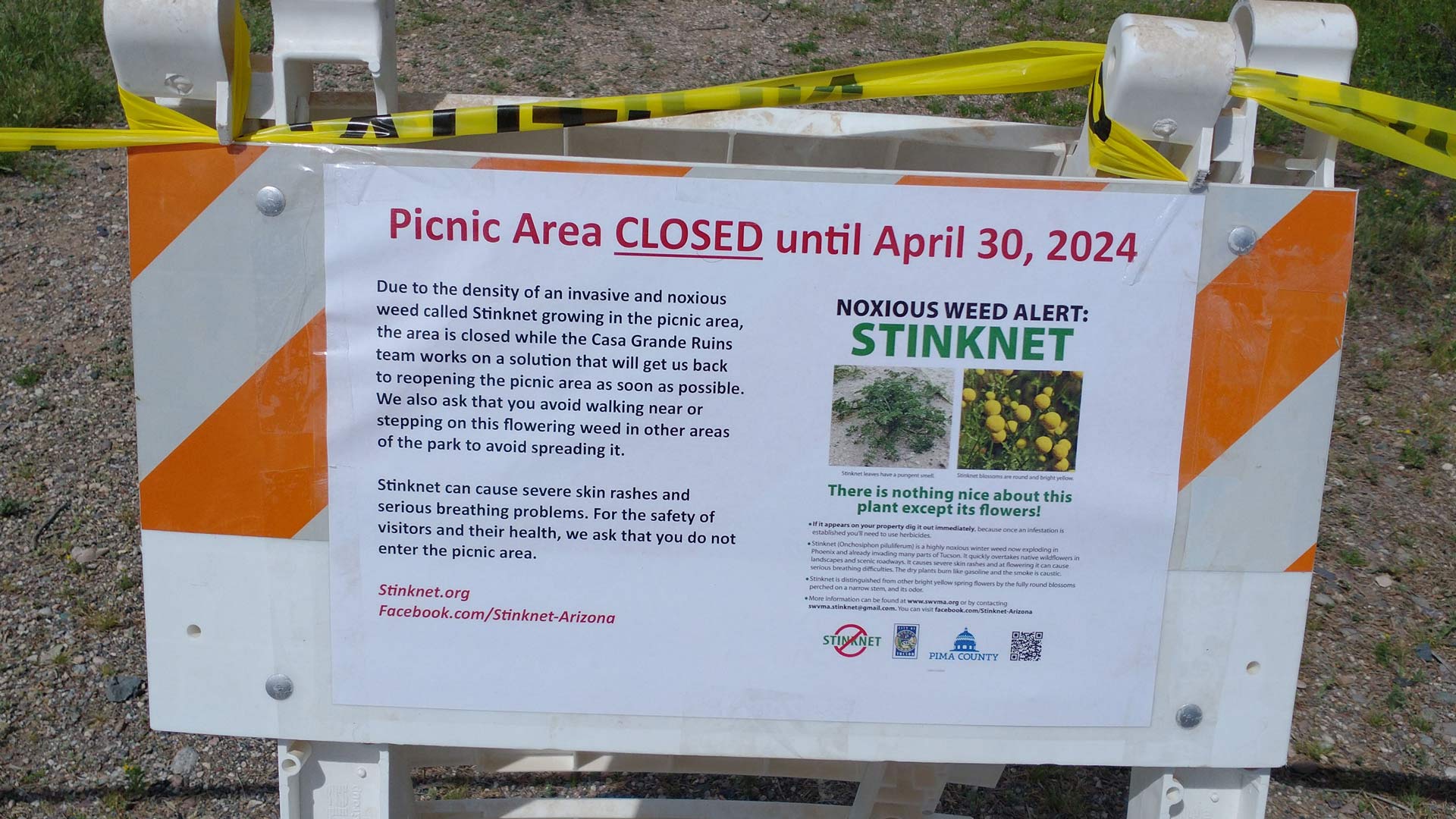

A picnic area has been closed during an eradication effort at this site in Pima County.

A picnic area has been closed during an eradication effort at this site in Pima County.

The way any of these three plants burn is cause for concern in the Sonoran desert.

"The main invasive species we're concerned about: buffelgrass, fountain grass, and stinknet, they all come from a part of Africa where fires are part of the lifecycle," said Tully. "So when those plants come in here, they will thrive off the fire, and our natives will not. And the habitat will be potentially transformed from saguaro vistas into a grassland."

And peak fire conditions are likely around the corner, according to Tom Dang, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service office in Tucson.

"We had our 15th wettest winter on record, so it was a fairly wet winter, and we can attribute that to El Niño. So the recent rains and the relatively cool weather does help to delay the fire weather season. I think in a lot of years in the past, we would probably be heading into fire season right now, and it just hasn't happened. I'm sure if you look around, you'll see all of the green and the grasses. And it's kind of remarkable for early April. That being said, things will dry out. We're not going to see much if any rain here for the next couple of months. So fire season is coming."

Dang said research shows a slight correlation between wet winters and dry monsoons, which could mean a prolonged fire season.

"Most people have been to the beach before and they're at least familiar with the idea of a land sea breeze. Part of the reason why it's comfortable out on the beach is because the basic science is when you have differential heating, like the sand heats up much quicker, much hotter than the ocean does, what happens is that warmer air lifts, and when that warm air rises over the sand, that cool ocean air comes in underneath The monsoon if you can think of it as just basically a very large scale land seabreeze. The desert southwest heats up during the summer. And when that heats up enough, you get that cool ocean air from the Gulf of Mexico or the Gulf of California that sweeps in. That's what brings the moisture for the fuel for thunderstorms in the monsoon for us." He said the cooling properties such as melting mountain snow can delay those conditions, but it is among several factors that change the severity of the fire season and the monsoon. Included in those are the presence of invasive plants.

"There's a lot of inter-connected pieces here. And it's not a one to one correlation, right? Like we can't just say wetter winter means we're going to see this date start for the monsoon or it's going to be this bad for fire weather. As we all kind of know, fires do tend to be human started, the vast majority of fires are started by humans and not by nature. So a lot of that is just dependent on, you know how conscientious humans are in terms of trying to control fire initiations.

Foley said they are hopeful that those conditions are creating plenty of fuel for wildfire, but also could help with eliminating stinknet.

"I think something that is really interesting to think about is that we had so much winter rain, right? The stinknet seed that was in the ground that was viable germinated and popped up. And so we're seeing a lot of stinknet. But the good news in my mind is that perhaps we're depleting that seed source in the soil. And so if we get ahead of it, and really make a lot of strides this year in removing the plants that are coming up, and preventing further seed from being deposited into the soil."

Both Tully and Foley said the best practice if you suspect that you have seen any of the three plants on public lands is to report them to land managers. Given the growing concern over stinknet, (the website stinknet.org)[https://www.stinknet.org/] has been set up to help people report the invasive plant so sites can be cleaned up and tracked for seeds.

"If you see stinknet in your yard, if it's a small amount, you can pull it out, just use gloves, and very importantly, report it on stinknet.org," said Tully. "Because stinknet is a little different than the others in that it's still, it's still possible to eradicate it here. With buffelgrass and fountain grass, we talked about management, we're not giving up. But it's about mitigating the risk. With stinknet, we still have a chance."

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.