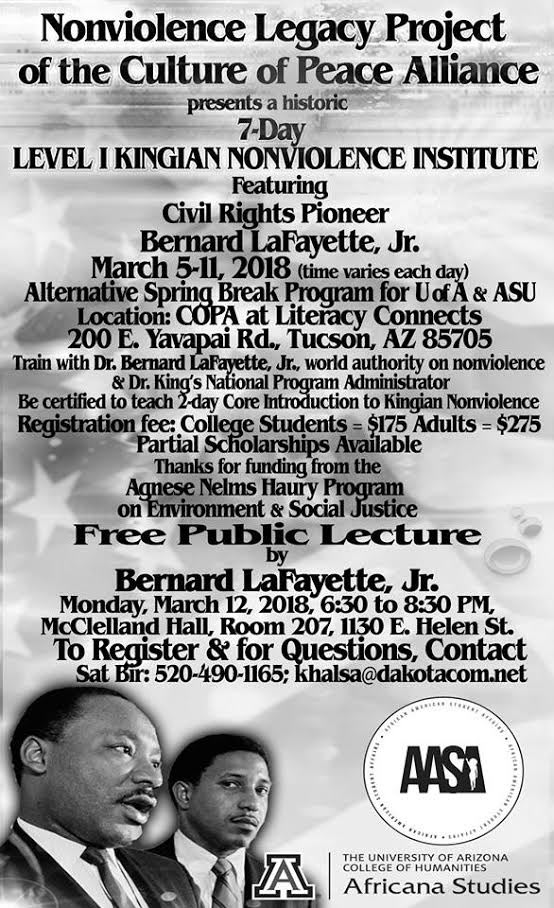

The morning he was assassinated, Dr. Martin Luther King, Junior told a young associate named Bernard Lafayette that their next task would be to institutionalize and internationalize the nonviolence movement. After King’s death, that became Lafayette’s life work. Today he is chair of the national board of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which was founded by King. On a recent visit to Tucson to speak at the Culture of Peace Alliance’s Nonviolence Legacy Project the civil rights pioneer sat down for an interview.

At 78 years old, Bernard Lafayette, Jr. comes across as laid back. He leans back in his chair and adjusts his cap. It has the words “Freedom Rider” emblazoned on the front. In fact, his new book, In Peace and Freedom, is all about those days. But Lafayette’s work is not just in the past. He’s been busy for the last 53 years building an international movement to teach Martin Luther King’s version of nonviolence. It’s called “Kingian nonviolence.”

Lafayette says, “We have institutions around the world. Like for example Alternatives to Violence Project and that’s in prisons. It’s in about 60 countries around the world, 30 states in the U.S. It helps the inmates learn how to manage conflict in a nonviolent way. “

They also train leaders around the world. Lafayette says that in September 2017, Muslims in north Nigeria gave a mandate to non-Muslims to leave the area, abandoning homes, businesses, and friends. They were given a deadline of October 1st and told if they didn’t get out they would be routed out violently.

“I got a team together and we went over and brought together leaders from various parts of Nigeria.” remembers Lafayette. “We trained tribal leaders, generals, and kings. On the second day of our training in Nigeria one of the leaders got a phone call from home saying his house had been invaded and his brother was killed and wife and children were on the run. All they wanted was the word from their leader, who was with us, to go after them. He said, ‘No, don’t do anything until I get back. I have found another way.’ This person had under his direct command 1.2 million armed troops. And as a result of the nonviolence training we were able to avert that situation.”

“People revert to violence when they don’t know what else to do. Violence is the language of the inarticulate. People don’t know how to talk to each other, they stay separated from each other and they form these false opinions and ideas about each other,” he says.

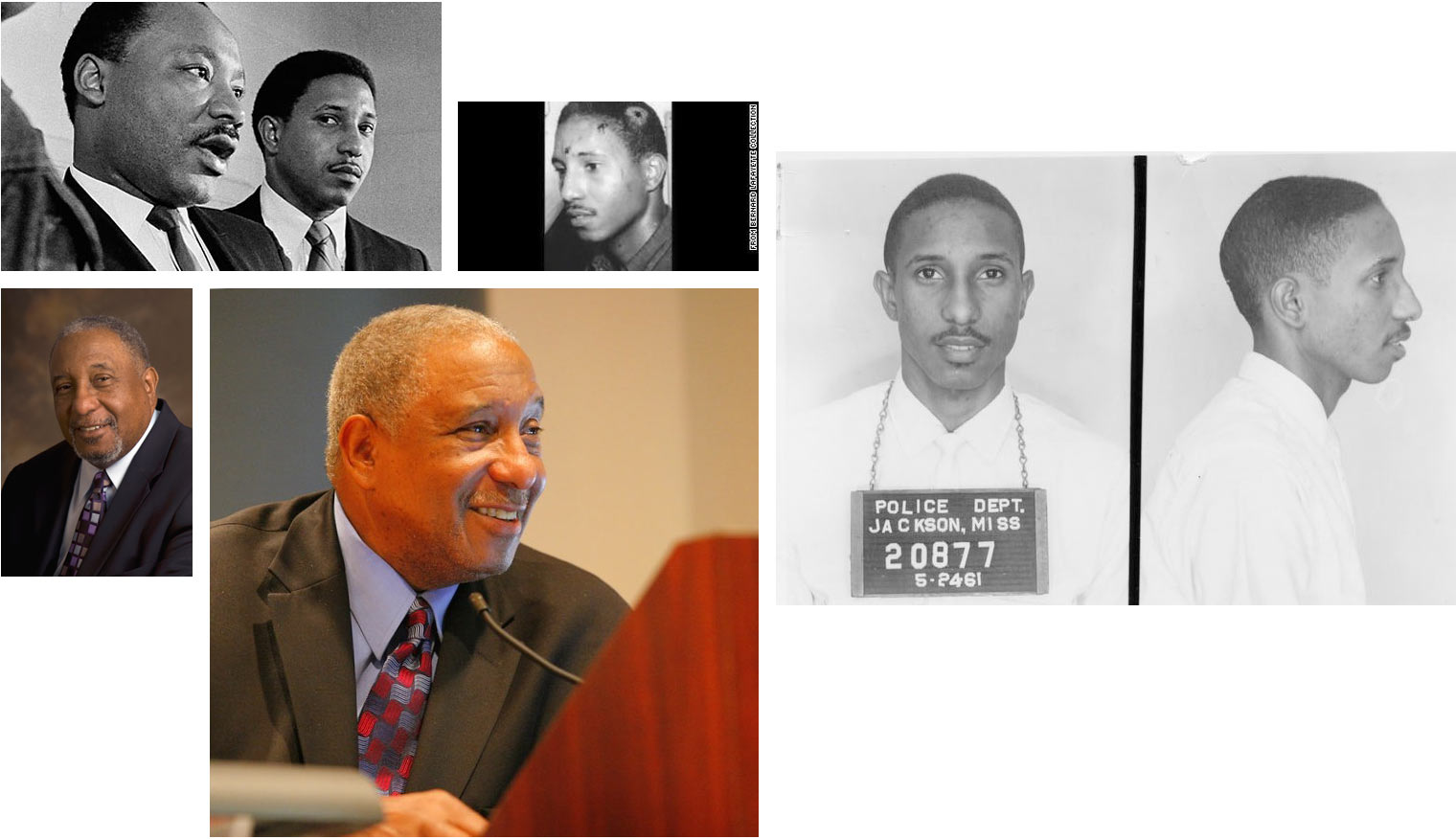

A collection of photos of Bernard Lafayette

A collection of photos of Bernard Lafayette

Lafayette had first-hand experience of this growing up in the segregated south in the 1940s. “I grew up in Tampa Florida. When I was seven years old I used to wake up early in the morning because I could smell the Cuban coffee being roasted,” he remembers. “So I got out of bed and decided that I was going to go walk around. And I found the merchants preparing to open up their stores. So I came up with the idea that these people might need some coffee. They didn’t have coffee machines in those days so I was Mr. Coffee. I would go and take orders and I would go down to Las Navidadas restaurant and put in my order. And then I would take it back to the merchants and there was 10 cents for the coffee and 10 cents for the delivery. Well, I was waiting on my coffee to be the served at the restaurant and I used to lean against a stool. I was kind of a short fellow and those were tall stools. And then eventually I would put my thigh up on top of the stool and rest it there for a while. Over a period of time I eased on up on top of the stool and then I was sitting there. And I remember even this day the moment of truth. The fellow was fixing the coffee. There was a huge mirror in front of him. He could look and see me behind him and our eyes met. And I saw him look toward the window to make sure no one saw me sitting on the stool. I continued to talk and talk and talk. We talked about everything else except sitting on the stool. When I sat on that stool the service was faster. (laughs) I hadn’t thought about it until now. It didn’t take as long for him to fix the coffee!’

That experience gave Lafayette a sense of confidence that he could be seen and treated like a human being.

“When I was growing up, Tarzan – by himself – he would whip an entire African tribe,” says Lafayette. “That gave credence to the fact that if you’re white you’re superior. What we have to do is continue to educate and expose people to a different point of view. I had other experiences that motivated me to get involved in the movement. I used to spend my time following behind my grandmother. So this time we were catching the street car – we call it trolley car. In those days, blacks had to go and put their money in the front in the receptacle by the driver and then we had to disembark and walk on the side of the streetcar to the back door. You had to sometimes run because the conductor after he got your money would close the door and take off with your money. So I used to run ahead, jump on the back steps so the door wouldn’t close. So I was running back there and my grandmother was running behind me. She fell! She was a large woman. I reached back to try to pick her up and then the trolley was moving and I tried to hold the door. I felt like a sword cut me in half. So I felt helpless. And I remember saying this to myself: I said, ‘When I get grown, I’m going to do something about this problem.’ “

Lafayette was 19 when he cofounded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He became a Freedom Rider. At age 22, he was director of the Alabama Voter Registration Campaign in Selma.

“I was really impressed with the power of nonviolence,” says Lafayette. “It’s a resource that you can use in your struggle where you don’t depend on any outside objects. In other words, you’re fully armed even when you step out of the shower in the morning – with the truth, with courage, with a vision, with a philosophy.

Lafayette survived an assassination attempt on the night Medgar Evers was killed. He says these experiences only deepened his conviction that nonviolence is the best path to meaningful social change.

We have had an escalation of violence in our society,” says Lafayette, “both in the everyday experiences of ordinary people, but also in terms of our media. Everywhere you turn. So I think we have to talk to our young people that they come to the conclusion that this is not very healthy for us. It contributes more to our demise than our rise. Therefore, if they develop an attitude of rejecting that then the change will come. I’m glad to see what’s happening in Florida with the high school students. The most important thing is not the experiences they’re having; it’s their interpretations of those experiences. That’s why is it important for us to talk to children. They’re experiencing things every day. It’s how you interpret the experience.”

Quoting his mentor Martin Luther King Jr., Lafayette says: “You cannot fight hate with hate. You can only fight and change hate with love. You can’t drive out darkness with darkness; only with light.” And like we say in the movement, you have to see the goal you’re trying to reach but you have to reflect that goal in every step that you make toward that goal.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.