VIEW LARGER

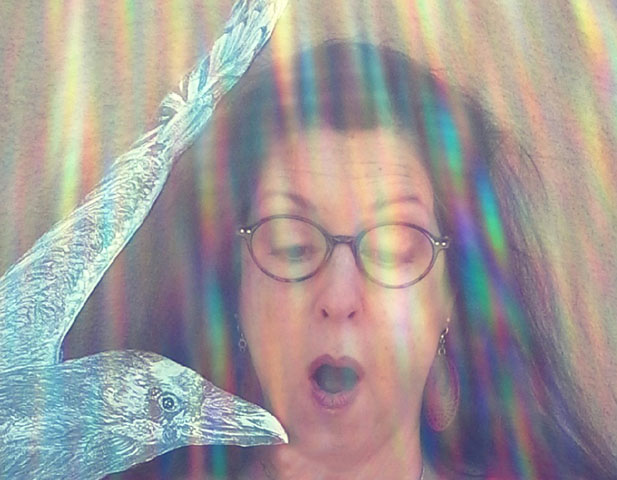

VIEW LARGER Artist and writer Beth Surdut listens to ravens and paddles with alligators in wild and scenic places. But she also knows that true adventure can be found in your front yard...

Listen:

The Art of Paying Attention: Javelinas

© Beth Surdut 2015

When I moved to Tucson, the neighbors warned me about some aggressive local visitors.

“Be careful near the mailboxes at night,” they said, showing me a nearby stand of once tall prickly pear cacti with scalloped cuts clear across at about 18 inches. “Don’t plant flowers out front, unless you want your pots scattered, and definitely no pumpkins for Halloween.”

So, of course, I really wanted to meet the marauders.

My cat and I were sitting outside the kitchen in bright daylight, watching a gila woodpecker making announcements as it sucked up sugar water from a hummingbird feeder, when I heard, “Goodbye, Javie.”

The tall wood fence around my yard blocks the view, but not the voices of a young mother next door who always seems to be teaching her little girl something as they go to and from their car.

“Goodbye, Javie. I hope you find your friends,” said the little girl.

Then, we smelled it—that earthy, rancid, wild thing odor.

VIEW LARGER

VIEW LARGER Cat looked at me with round blue eyes, twitched his pink nose, and took off into the house as I leapt for the gate that opens towards the voices. I opened it a crack. A musky-scented, mid-sized peccary—maybe 40 pounds-- was trotting by on the other side of a wire fence.

My hand was already reaching for the camera as I slid into shoes and out the front door.

Javie was standing right there, all alone, about ten feet away. Warnings trotted through my head: “You have to be careful. Javelinas are dangerous. Don’t mess with them.”

Yes, they can be aggressive if they feel threatened, and have the canines and tusks to back that up, and they are wild, interesting, and cute. This one was looking at me like someone who’d neglected to put on their glasses, which is understandable. Collared peccaries have poor eyesight, fair hearing, and an excellent sense of smell—they have scent glands on their rumps that they use for marking territory and recognizing each other. But this little laggard didn’t seem to smell what I saw out of the corner of my eye. Over to my left, lots of little hooves were trotting past the far side of my neighbor’s truck, and they were all heading away from us.

Javie ambled a few feet to the right.

“I’ll be right back,” I told the javelina, as if it could understand me.

I skirted the truck, turned left around a tall fence, and stopped. About a house-length away, a mother javelina was standing in the dirt driveway, nursing her two babies. The rest of the herd was just ahead of her. None of them chattered an alarm call—which they do by opening and closing their mouths and rubbing their tusks together-- so I quickly took two photos and quietly walked back to my place—to Javie, who was now right in front of my door.

I stopped. Waited.

Javie cocked his head and squinted.

“Whatcha gonna do, Javie?”

The animal breathed out short puffs with each step as he or she moseyed past the door, stopped, moseyed enough that I could walk into my studio. As I looked out my window, Javie’s scented rump was rounding the corner in the opposite direction.

“Goodbye, Javie, I hope you find your friends.”

- by Beth Surdut

Note to observers: Peccaries - collared or not - are not pigs (Suidae). They are Tayassu — Angulatus or Tajacu. Besides internal differences, they have small ears, hard to find tails, longer thinner legs than a pig, and they sport thick, bristly, dark grey coats with a ring of white fur around their neck, which looks a lot like a collar.

Oct 20, from 3 to 4:30 PM, Beth Surdut leads a workshop on The Art of Paying Attention-- Critter Tales: Yours, Mine, and Ours at the Tucson Botanical Gardens during National Phenology Week. This workshop will explore improving observation skills through exercises and storytelling. Surdut adds "Come share your backyard critter and habitat stories —off the cuff is just fine! Do bring a notebook."

Find more of Surdut's drawings - and true stories about spirited critters - at listeningtoraven.com and surdutblogspot.com.

Beth Surdut's illustrated work Listening to Raven won the 2013 Tucson Festival of Books Literary Award for Non-Fiction. Elements of her raven clan have appeared in Orion Magazine, flown across the digitally looped Art Billboard Project in Albany, New York and roosted at the New York State Museum in an exhibition of international scientific illustrators.

"The Raven" segment of Encyclopedia of Santa Fe and Northern New Mexico by Mark Cross is illustrated with The Reason Why along with her explanation of Raven calling her to the Southwest to draw and collect first person stories of interactions with this clever corvid and iconic spirit guide.

VIEW LARGER

VIEW LARGER

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.