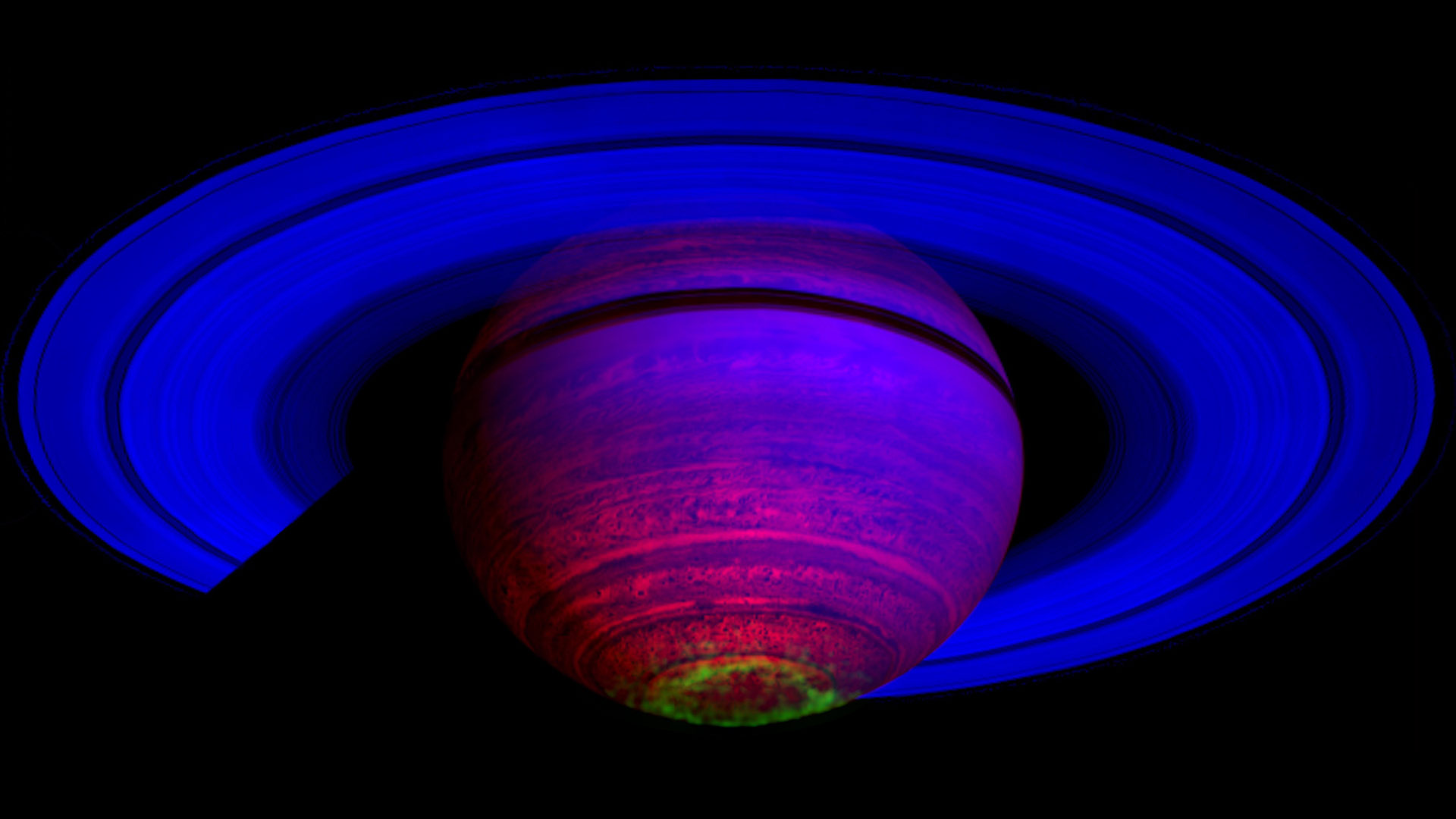

This false-color composite image, constructed from data obtained by NASA's Cassini spacecraft, shows the glow of auroras streaking out about 600 miles from the cloud tops of Saturn's south polar region. The image was taken by the University of Arizona-led Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer.

This false-color composite image, constructed from data obtained by NASA's Cassini spacecraft, shows the glow of auroras streaking out about 600 miles from the cloud tops of Saturn's south polar region. The image was taken by the University of Arizona-led Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer.

When NASA’s Cassini spacecraft takes its fatal dive into Saturn, Sept. 15, a University of Arizona scientist’s instrument will be the last to provide images of the ringed planet.

Planetary science and astronomy professor Robert Brown was at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory before the Cassini mission was proposed in the 1980s. The instrument he designed, built and operates is the Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer, called by its acronym, VIMS. It is a collaboration between U.S. and European space agencies.

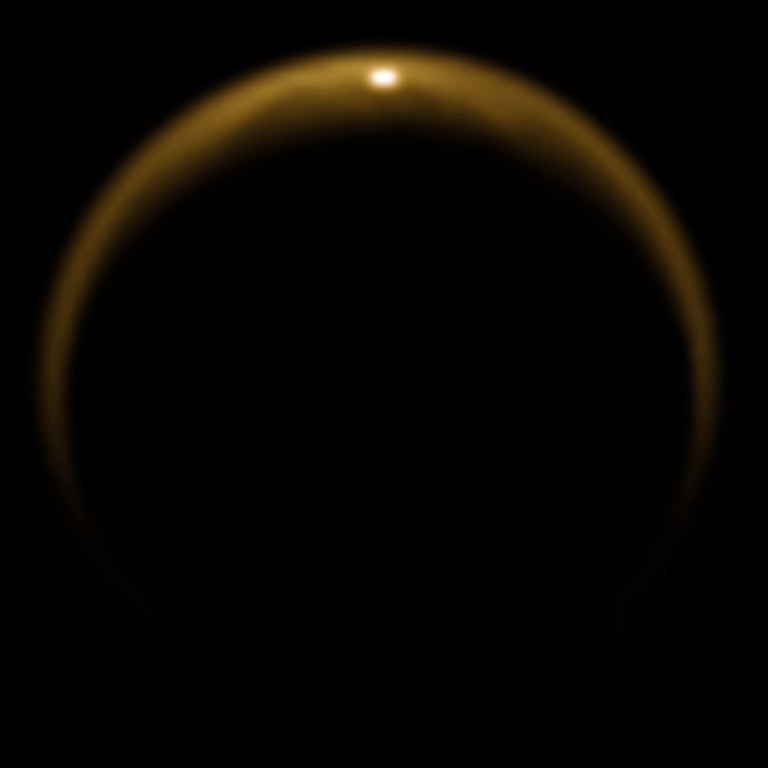

Brown said among VIMS’ many accomplishments was taking the first measurement of a glint of light off an extraterrestrial sea, the glassy liquid methane and ethane surface of the moon Titan.

“From my perspective, it was one of the most interesting and awesome images to come out of the mission, and it gives you a real strong sense of just how bizarre and how beautiful the solar system is outside of our tiny little environment here,” Brown said.

VIEW LARGER Sunlight glints off a lake on Titan, a moon of Saturn, in this photo taken by VIMS in 2009. It confirmed the presence of liquid in the moon's northern hemisphere.

VIEW LARGER Sunlight glints off a lake on Titan, a moon of Saturn, in this photo taken by VIMS in 2009. It confirmed the presence of liquid in the moon's northern hemisphere.

Brown called VIMS the Swiss Army knife of the spacecraft because of its versatility throughout the 13-year Cassini mission. It’s been taking pictures in wavelengths well beyond what the human eye can see.

Brown’s instrument provided clues to chemical and surface compositions, atmospheres and physical processes that modified the surfaces of Saturn and its moons.

And it will work up until the very end, sending back to Earth the final images before the spacecraft crashes into the planet.

Brown, his VIMS team and other Cassini mission members will be at JPL in the early hours of Sept. 15 to witness the end of the lengthy and productive mission.

“The impact site on Saturn is going to be on the dark side, and because we can see in the dark, we’re going the take the final images of the impact site. And then we will go up in smoke with the rest of the spacecraft a few hours later,” Brown said.

Cassini launched in 1997 with a four-year primary mission once it reached the planet in 2004. The space agency extended the science mission to continue to study Saturn and its moons.

It will crash into the planet so Saturn’s moons, future targets for exploration, will not be contaminated by the wreckage.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.