Author & wildlife illustrator Beth Surdut now calls Tucson her home, but she has lived in many places. This year's violent hurricane season led her to recall a time more than a decade ago, when she learned some wisdom about surviving the storms...

For more than two years, we've been telling you that Beth Surdut listens to ravens, and has paddled with alligators in wild and scenic places. The Myakka River State Park in Sarasota, Florida recently reopened following Hurricane Irma. In 2005, she first met that river's most famous - and formidable - creatures...

Sarasota Hurricanes

© Beth Surdut, 2017

Soon after I moved to Sarasota, Florida in January 2005, months before hurricane season, I was welcomed into a writing group an hour south, in Punta Gorda. In August of 2004, Hurricane Charley had swirled and crushed and ripped through there so fiercely, that parts of town looked liked there'd been a war.

Sitting around under the stars, poets and songwriters offered me moonshine and story after story about surviving Charley--sort of. When you watch your house blow away, when you take cover in the bathroom with your kid and your dog as your roof rips off, what remains is PTSD.

I said, "I just moved here. Should I turn tail and run now?"

They chuckled and someone said, "Nah. But you should move down here with us and when the time comes, we'll tell you which way to run."

Except the fierceness can change course in an instant and you might be running right into danger, not away from it. So you hear "hunker down" a lot.

I am not, by nature and design, a worrier, but the uncertainty of hurricane season -- the planning, second-guessing, preparation, and knowledge that it could be all for nought -- is like a festering tiny splinter that you'll never quite dig out.

But let me tell you about the river…

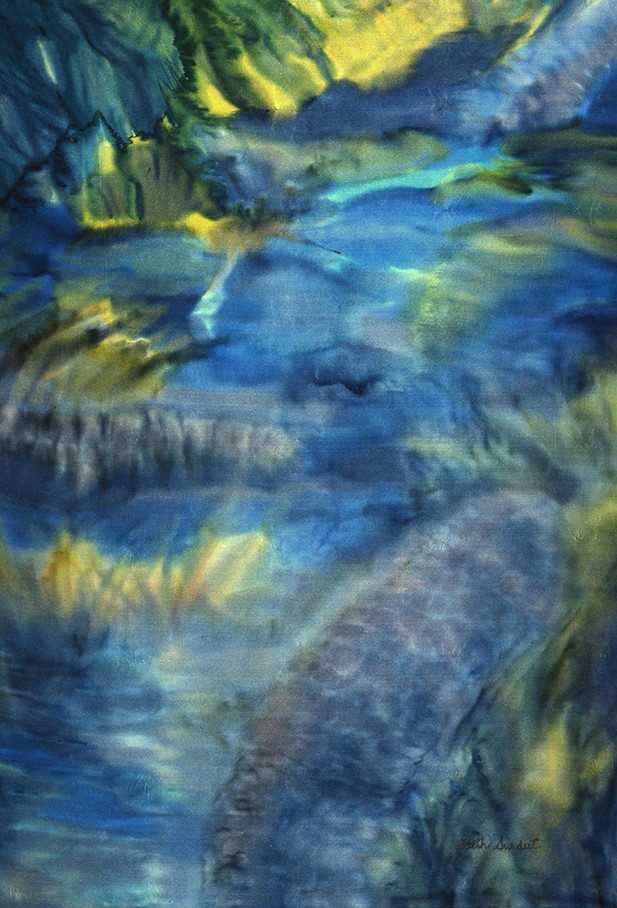

The Subtlety of Gators

© Beth Surdut, 2017

"Don't be scared," said the guide in the boat next to me as the alligator lunged towards my kayak.

"I'm not scared," I whispered, looking down at the huge prehistoric head right next to my hip. "I'm petrified."

I watched the gator swim past, gliding parallel to my little red tub toy of a boat.

VIEW LARGER

VIEW LARGER The guide’s breath whooshed out. "I'm sure glad he didn't get scared and try to climb over our boats."

Um, yeah, me, too.

That was my first time paddling on the river, and I was hooked.

VIEW LARGER

VIEW LARGER Florida’s Myakka River is 68 miles long, and lives up to its official designation as wild and scenic. It’s a feast for gators and birds--I just didn't want to be the main course. The next day at an orchid sale, I heard someone yell, "Hey, Gator Girl!"

It was one of my newly met paddling buddies. My behavior on the river--shock masquerading as serenity--earned me a new moniker.

That first time stretched into three years paddling the Myakka, a place that never disappointed, always enchanted. Herons abound--Great Blues, Whites, Tri-colored, Green; heavy-bodied wood storks whose wings whoosh loudly as they loft; goofy and gorgeous pink roseate spoonbills swishing their spatulate bills in the water; bold ospreys who would swoop down right in front of my boat, and rise up with a fish grasped in their talons; anhingas, also great fishers, standing on branches drying their outstretched wings. And more species of birds than I can count.

VIEW LARGER

VIEW LARGER I only went with a group and a guide that first time. Most often I paddled with one boon companion in a canoe. I like the higher sides, especially when a gator gets close and lunges up out of the water, jaws agape. It’s a rare occurrence, especially if it’s not mating season when the big boys bellow "Stella" in their own version of Streetcar Named Desire.

VIEW LARGER

VIEW LARGER The dark reflective waters usually hide who's swimming under or beside the boat. Eyes, heads, and snouts dot the surface and often sink like submarines as we approach. My favorite prehistorics, as I came to call Alligator mississippiensis, became the subjects of one of my favorite paintings -- Myakka: the Subtlety of Gators.

VIEW LARGER

VIEW LARGER I have seen the spectrum of life—pop-eyed baby gators with stripes still visible on their tails, and once, a 12-foot gator corpse feasted upon by black vultures.

They usually amuse me with their hopping, "dum-de-dum, de-dum-de dum" gait, but watching them feed is a dark story that whispers fear around a campfire.

VIEW LARGER

VIEW LARGER And then there are the behavior-challenged critters that I would like to discuss with Darwin…

A curious young gator, maybe four feet long, leaves the shore and swims quickly towards our canoe, his tail snaking through the water. In rare moments of clarity, the dappled sun lights his movements just under the surface. Soon as he's close enough to figure out what we are, he swims parallel to the boat.

VIEW LARGER

VIEW LARGER The birds have gone silent and instead of their songs, we hear some recidivist rehab diva's voice scratching nature till it bleeds. The gator submerges, now invisible, as we round the bend where the air is abraded with the scent of burning tobacco.

There’s one man standing--well, sort of swaying--in thigh-deep water, his white skin glowing in the tannin-dense river. One hand is conducting with a cigarette, and he's using the beer in the other hand as ballast.

“There’s a gator heading in your direction,” I call to him, and the idiot, showing off for his beer-can buddies in their boat, yells, “Great! I’ll go meet it!” and dives under water.

I ply the paddle deep and fast, saying to my companion, “This could be a Darwin Award moment and I don’t want to see it. Just keep paddling.” Far be it from me to get in the way of that guy's personal freedom.

I didn’t hear any screams, so I guess the idiot and the gator survived.

VIEW LARGER

VIEW LARGER You’d think that telling “gator and the idiot” stories would be cautionary tales, but a ranger at Myakka State Park told me that there are people who emulate whatever bad behavior they hear about. Tell them not to feed gators, and picnickers are right on the river bank tossing in hot dogs. They might as well be tossing in their kids and canines. There’s even a warning sign showing some small poodlish creature as temptation.

The sad reality is that an alligator not only comes to associate humans with food, but doesn’t distinguish between the food and the hand that holds it. Potentially, you’re just one big snack, bubba.

If a gator grabs a human, even if it’s the human’s fault, the alligator is removed—that means killed.

VIEW LARGER

VIEW LARGER On a deliciously moist day, I counted 14 gator heads in the water around me. Squinting into the drapery of Spanish moss hanging from live oaks, I saw vultures gathered in the shadows. I stopped counting when I got to 48 vultures in the trees and on shore. I could discern no carrion in sight or scent. I never felt threatened, but I did keep paddling, in case they mistook me for dessert.

VIEW LARGER

VIEW LARGER Visual storyteller Beth Surdut invites you to observe, with unbounded curiosity, the wild life that flies, crawls, and skitters along with us in our changing environment. From exotic orchids and poison dart frogs to local hawks and javelinas, Surdut illustrates her experiences with wild and cultivated nature by creating color-saturated silk paintings and detailed drawings accompanied by true stories.

You can find Surdut's drawings - and true stories about spirited critters - at listeningtoraven.com and surdutblogspot.com.

Beth Surdut's illustrated work Listening to Raven won the 2013 Tucson Festival of Books Literary Award for Non-Fiction. Elements of her raven clan have appeared in Orion Magazine, flown across the digitally looped Art Billboard Project in Albany, New York and roosted at the New York State Museum in an exhibition of international scientific illustrators.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.