Myriam Moscona is an author, journalist and poet who lives in Mexico City. Her parents were Sephardic Jews from Bulgaria.

Myriam Moscona is an author, journalist and poet who lives in Mexico City. Her parents were Sephardic Jews from Bulgaria.Myriam's Moscona home was filled with the sounds of different languages while growing up in Mexico City, where she was born in the 1950s.

Moscona's native tongue is Spanish, but she also studied Hebrew in school.

Her parents were Jewish immigrants from Bulgaria who left Europe after World War II and settled in Mexico City.

"They spoke Bulgarian between them, Ladino with the grandmother, and Spanish," Moscona says.

"My mother was an opera singer so she spoke perfect English, perfect German, perfect Italian."

But the language that stood out most to the little Latin American girl surrounded by European adults was Ladino, also known as judeoespañol, or Judeo-Spanish.

It was spoken by her grandparents, who had joined the family in Mexico.

Ladino traveled to Europe and other parts of the world with Sephardic Jews that were expelled from Spain in the 1400s. They kept it alive in countries such as Greece, Serbia and Tunisia.

It's very similar to modern Spanish but retains the words and spelling from another era.

"They spoke in that strange language that was alive with them since they were children. It was that heritage of life in Spain 500 years ago," Moscona says.

Moscona was intrigued by her elders' language, customs and religion, especially after losing her grandparents at an early age.

Her father died soon after that, when Moscona was 8 years old, and her mother passed away when Moscona was 20.

When she was older, as a professional journalist, writer and poet, Moscona conducted research about her family's heritage and language and was able to travel to Bulgaria in 2006.

She met with Ladino-speaking populations, explored the countryside, and looked for the former homes of her parents and grandparents.

"It was not the most beautiful trip I ever did, but the most emotional one," she says

When she returned to Mexico City, Moscona decided to write a book that is inspired by her life, although it's not a biography.

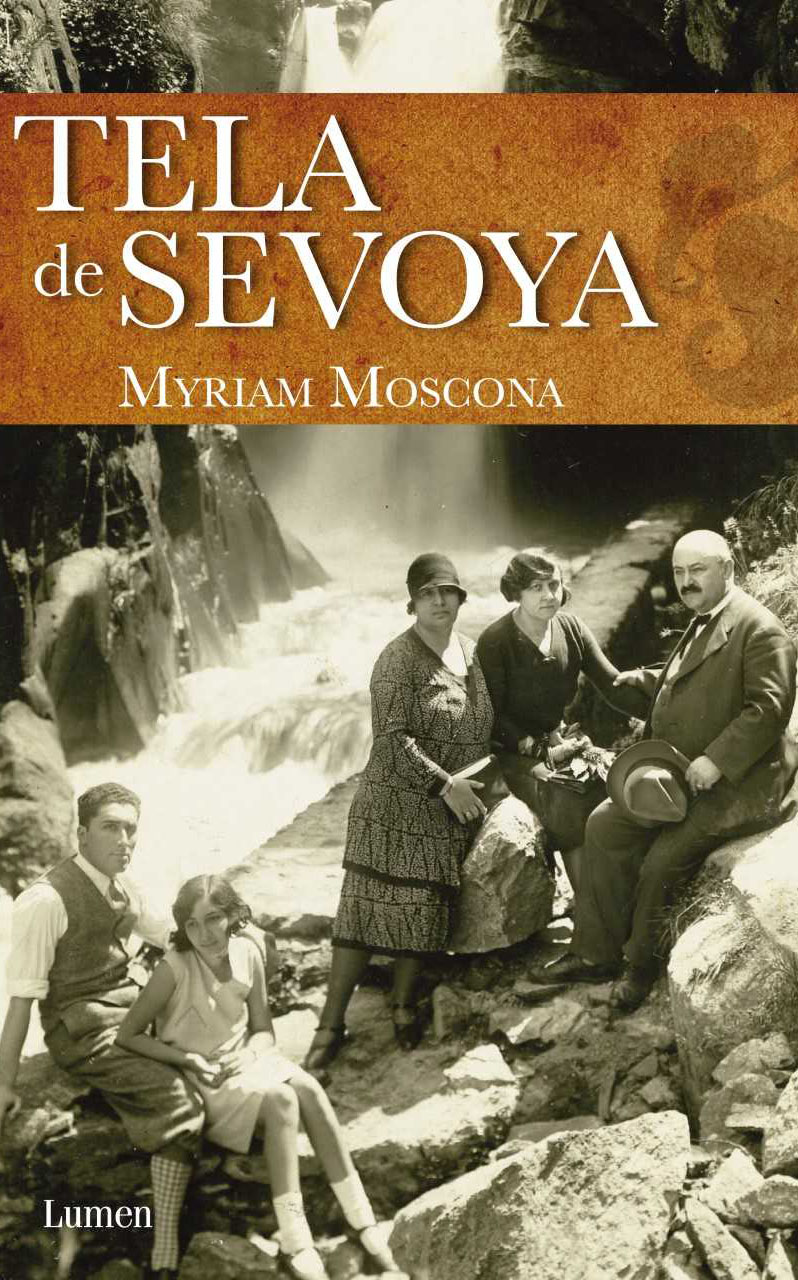

VIEW LARGER The Ladino title "Tela de Sevoya" would be written as "Tela de Cebolla" in modern Spanish. The book is called "Onioncloth" in English.

VIEW LARGER The Ladino title "Tela de Sevoya" would be written as "Tela de Cebolla" in modern Spanish. The book is called "Onioncloth" in English. Moscona hopes the story of a little girl and her fascinating relatives will reveal how people are more similar than different, regardless of their own languages, cultures or religions.

She says another goal is to draw attention to a language whose use has been declining as fewer people pass it on to younger generations.

"What I felt is that that fire was dying and what I had to do is something just to leave a memory of that fire," she says.

Moscona's book is called "Tela de Sevoya" in Ladino, which would be "Tela de Cebolla" in modern Spanish, and has been translated to "Onioncloth" in English.

"The only thing I know to do is write so what I want is to leave a memory of this language," she says.

Author Myriam Moscona will be in Tucson on Wednesday, Feb. 27 for a trilingual reading and discussion of her book at the Jewish History Museum.

She will also attend another function at the University of Arizona's Poetry Center on Thursday, Feb. 28.

Myriam Moscona's parents were born in Bulgaria and settled in Mexico after World War II.

Myriam Moscona's parents were born in Bulgaria and settled in Mexico after World War II.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.