Scott Warren outside U.S. District Court Nov. 20, 2019, following acquittal in the government's second trial.

Scott Warren outside U.S. District Court Nov. 20, 2019, following acquittal in the government's second trial.

Humanitarian aid trials

The Tucson trials this year of humanitarian aid worker Scott Warren stirred controversy and drew national attention. Warren is an Ajo educator and volunteer for local aid group No More Deaths. The U.S. Border Patrol apprehended Warren at the No More Deaths headquarters in Ajo in early 2018, where they found two undocumented migrants. Warren had given the men food, water and shelter.

Scott Warren was accused of one count of conspiracy to transport undocumented migrants — a 10-year sentence — and two counts of harboring: a total of three felony charges. He faced up to 20 years in prison. He also faced separate misdemeanor charges for trespassing by driving on restricted roads in the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge and leaving water and supplies in a wildlife area.

His first trial on two counts of felony harboring and conspiracy resulted in a hung jury in June. In his second trial, last month, the conspiracy charges were dropped and he was found not guilty on charges of harboring. He was found guilty of the driving misdemeanor and will be sentenced in February.

No More Deaths volunteers stand in support of Scott Warren during his second trial in November 2019.

No More Deaths volunteers stand in support of Scott Warren during his second trial in November 2019.

Sara Vasquez was one of the No More Deaths volunteers standing in support of Warren outside the courthouse during his November trial. Vasquez, a physician, said she’s seen all kinds of things during her time volunteering on the border, including people lost in the desert.

"I've come across people who are very dehydrated, thirsty and hungry, lost and very frightened," Vasquez said. "I've seen people who are injured, with feet that were severely blistered or bruised, people with sprained ankles, people with sprained knees. I've found bodies, I've found human remains."

She said prosecution of her fellow volunteers won’t deter her or others from continuing the work.

"Because the fact is that our migrant brothers and sisters are still in distress, still crossing, still coming. You know, the situations in which people find themselves living is so desperate that people are still willing to risk their lives."

Brit Hessler, another No More Deaths volunteer, said Warren became the face of humanitarian aid work.

"I think that right now, our current administration is looking for someone to be a symbol for all this," Hessler said. "I think that they felt like they had a good case. Because what’s on trial right now is not actually Scott Warren. It’s all of us. It’s humanitarian aid."

Hessler pointed out that humanitarian aid work, like what No More Deaths does, is a very old practice.

"There are lots of people doing this work," Hessler said, "and have been doing it for generations, whether they are associated with a humanitarian aid group or they’re just a family or they’re just an individual that goes out and does this from their back door."

Emily Saunders is an Ajo resident who volunteers with a few humanitarian aid groups, including No More Deaths. She’s also Scott Warren’s partner. She said humanitarian aid is a part of life in Ajo.

"It’s really common to have someone knock on the door of someone who lives here asking for food and water and help," Saunders said, "or to be driving down the highway and encounter someone who’s lost."

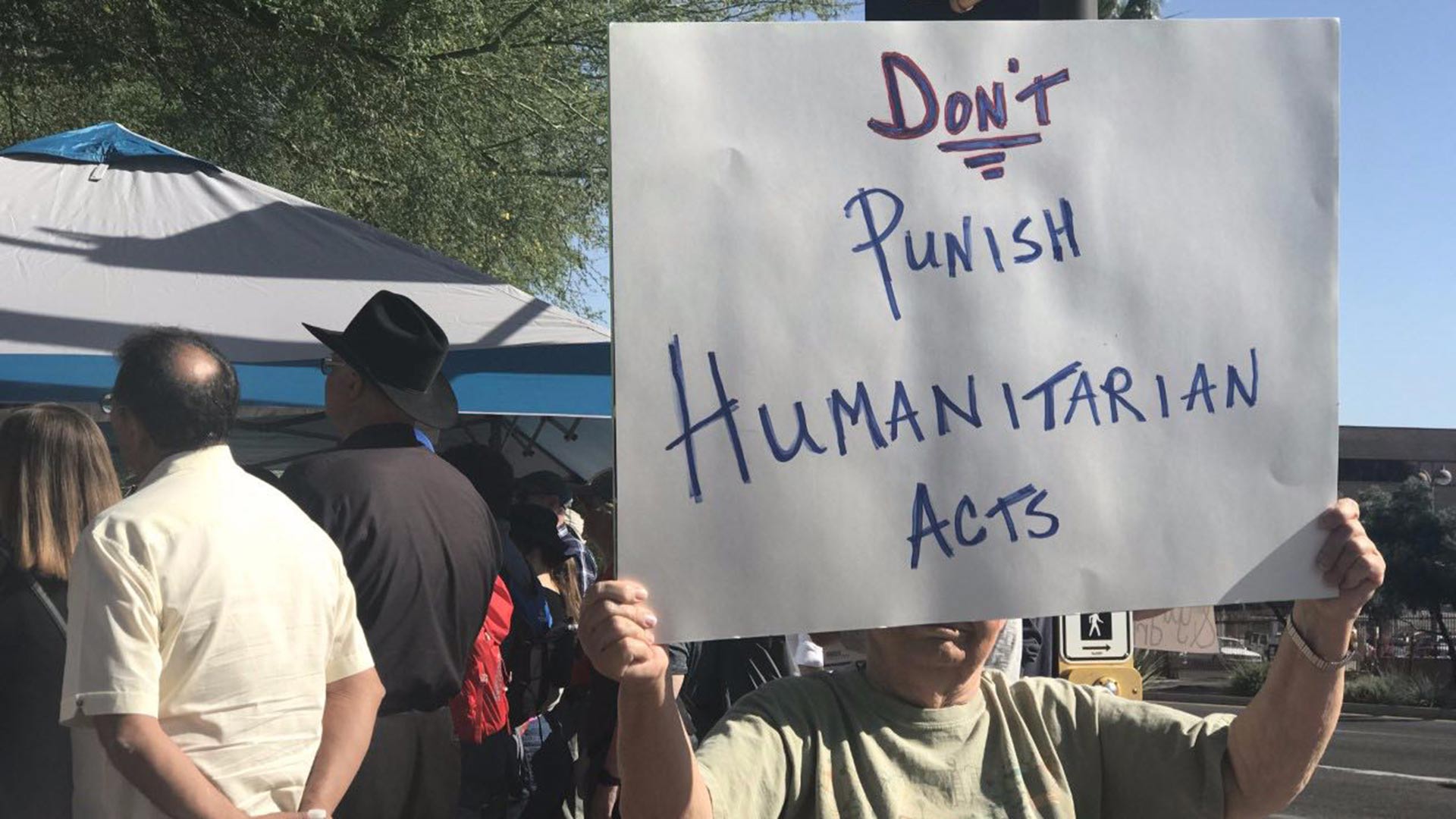

VIEW LARGER A woman holds up a sign support of Scott Warren reading, "Don't punish humanitarian acts," June 3, 2019.

VIEW LARGER A woman holds up a sign support of Scott Warren reading, "Don't punish humanitarian acts," June 3, 2019. Eight other humanitarian aid workers were charged with criminal violations for their activities on the Cabeza Prieta wildlife refuge. Four were convicted of misdemeanor charges, while the other four settled for civil infractions.

Heather Sechrist is the criminal chief for the U.S. Attorney’s Office of Arizona. She couldn't speak specifically about the Warren trial but said intent matters in deciding these cases.

"But if someone is violating the law, if somebody is harboring an individual and their purpose is to help that individual elude law enforcement to stay in the country illegally, then it doesn't matter how they characterize themselves," she said, whether it's as a humanitarian aid worker or anything else.

In April 2018, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions declared a zero tolerance policy on immigration-related offenses and ordered federal officials to prioritize prosecutions of undocumented migrants with criminal convictions. Syracuse University reported a 16% increase in 2018 over the year before in prosecutions of people accused of bringing in and harboring migrants.

Sechrist said Session's memo instructed federal officials to have a renewed commitment to prosecuting people in the country illegally with criminal backgrounds.

"When you read the zero tolerance policy, it doesn't make mention of anything about harboring or alien smuggling or transporting illegal aliens, much less any mention of humanitarian aid workers," she said.

Sechrist said in just the last few weeks, the federal government has prosecuted felony offenses for previously deported people back in the country illegally who were also convicted of crimes that include domestic violence, sexual assault, armed robbery and drug trafficking in Arizona.

Before trial, Scott Warren's lawyers tried to get the case dismissed by invoking the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. They argued Warren provided humanitarian aid because of his spiritual beliefs. The judge rejected that argument as grounds for dismissal but said the attorneys could bring it up during the trial. They did, and the judge found Warren not guilty of one misdemeanor charge based on those arguments.

Katherine Franke is a law professor and faculty director of the Law, Rights and Religion Project at Columbia University. She joined four other professors at Columbia in filing a brief in Warren's case supporting his use of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. When many people think of religious liberty, Christianity often comes to mind. But Franke says that’s just because of recent history.

"The Christian right, the Evangelical Christian right, has done a very effective job of capturing the very idea of religious liberty. ... But if you look historically at the way in which we have protected religious liberty in this country going back to even before the founding of the country, religious liberty rights were really put in place in order to protect religious minorities," Franke said.

She said people can't just use the religious freedom argument to try to get away with something. "The requirements for getting a religious exemption are actually quite stringent," she said.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.